Since the mid-20th century, the international monetary system has exacerbated inequality by design. At its core there is a structural asymmetry: a privileged few countries have the advantage of borrowing cheaply and investing in relatively more profitable assets, securing income inflows. This advantage was first described in the 1960s as the “exorbitant privilege” of the United States, whose role as issuer of the world’s main reserve currency allowed it to pay less on what it owed than it earned abroad. What began as a U.S.-specific feature has since become a structural privilege of the rich world. Europe, Japan, and other advanced economies now enjoy similar benefits, while poorer countries face the opposite burden: they pay higher interest on their debts, hold assets that yield little, and transfer income abroad each year. In effect, rich countries have become global rentiers, systematically extracting resources from the rest of the world.

This chapter, based on Nievas and Sodano (2025), documents how the system works. First, we show how the U.S. privilege widened into a collective advantage for the richest 20% of countries. Second, we highlight a paradox: privilege persists even for a net debtor region such as North America & Oceania. Third, we explain how advanced economies became financial rentiers by design, through currency dominance, portfolio asymmetries, and institutional rules that perpetuate their advantage. Fourth, we examine how these asymmetries act as barriers to development, draining resources from poorer nations. The chapter concludes by arguing that these dynamics amount to a modern form of unequal exchange, echoing earlier colonial transfers. Finally, it calls for urgent reform of the international monetary, financial, and trade systems to address and reduce these inequalities.

The U.S. exorbitant privilege has evolved into a structural privilege of the rich world

The idea of “exorbitant privilege” was coined in the 1960s to describe the United States’ unique position in the world economy. This was not the result of singularly skillful investments but of the central role of the dollar. Given its preeminent role in the international monetary and financial systems, investors and central banks worldwide considered U.S. assets safe and liquid, and the country could therefore borrow at very low rates and reinvest abroad at higher returns.

New evidence unearthed by Nievas and Sodano (2025) shows that this advantage has expanded well beyond the U.S., which now owes 2% of its GDP to this exorbitant privilege. Figure 5.1 illustrates how the privilege has evolved into a broader feature of the global economy. Japan now records the largest benefits of this skewed system, close to 6% of GDP, while the Eurozone also has positive balances (about 1%). By contrast, emerging economies remain at a disadvantage: BRICS1 countries record persistently negative excess yields, averaging 2% of GDP.

Figure 5.2 details this pattern further still. When grouped by income, only the richest 20% of countries, which are home to one-fifth of the global population, consistently present positive excess yields, equivalent to approximately 1% of GDP. The rest of the world records deficits ranging from 1% to 3% in the last decade.

Regionally, North America & Oceania, East Asia (excluding China), and Europe stand out as the main winners. Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, South & Southeast Asia, the Middle East & North Africa, Russia & Central Asia, and China remain net losers. Far from being a U.S. exception, exorbitant privilege has become a structural privilege of the rich world, reinforcing global inequality rather than narrowing it.

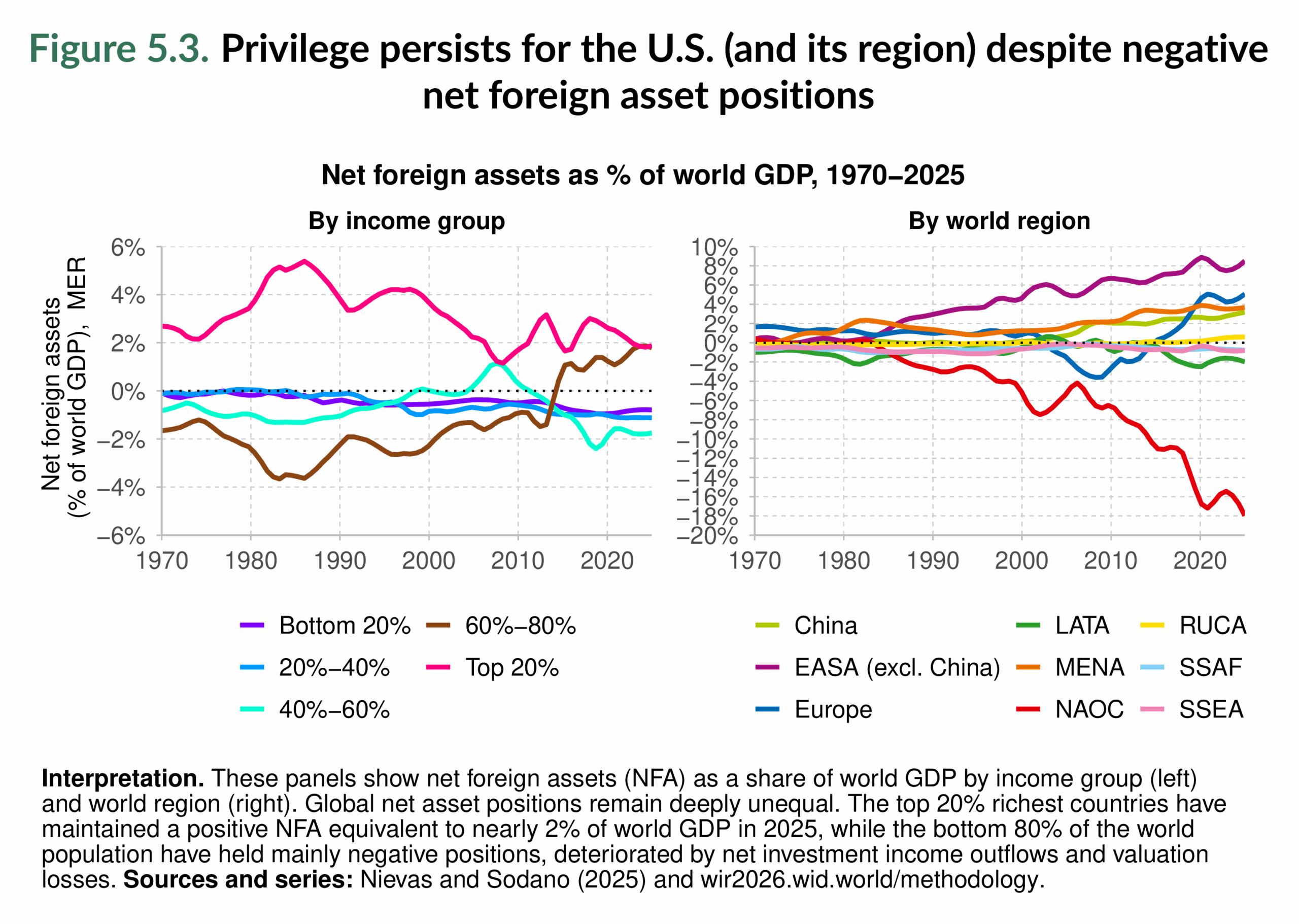

One of the paradoxes of global finance is that some regions can hold negative net foreign asset (NFA) positions yet still earn positive net investment income. The North America & Oceania region is the clearest example. It has long been the world’s largest net debtor, with foreigners owning more assets in North America & Oceania than what residents from North America & Oceania hold abroad (Figure 5.3). Yet year after year, the region records a surplus on net foreign capital income due to excess yields (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 also shows how the richest 20% of countries consistently record positive income flows. Meanwhile, the bottom 80% are persistent net debtors and face negative income balances, reinforcing their disadvantage.

Rich countries are global financial rentiers by political design, not because of market dynamics

Figure 5.5 to Figure 5.7 reveal why the exorbitant privilege has persisted and extended: the global financial and monetary system has been deliberately structured to favor advanced economies. Their role as issuers of reserve currencies, the composition of their external portfolios, and the cost asymmetries between assets and liabilities combine to make them global financial rentiers.

Figure 5.5 documents a foundation of this privilege: currency dominance. Over the last few decades, the U.S. dollar has remained the predominant medium of trade invoicing, financial asset denomination, and central bank reserves. The euro has also become, to a lesser extent, a major player since its creation. Other currencies play only marginal roles. This institutional inequality ensures persistent demand for dollar- and euro-denominated assets. This leads to persistently lower borrowing costs for the U.S. and Eurozone, whereas other economies are more exposed to debt in foreign currencies and vulnerable to exchange rate fluctuations.

Figure 5.6 highlights the composition of cross-border portfolios. Rich countries hold equity and foreign direct investment on the asset side, which typically have higher returns, while their liabilities are predominantly low-cost debt securities. Poorer countries show the mirror image: they hold large shares of reserves, safe but low-yielding, while issuing liabilities in the form of high-cost debt and inward foreign direct investment (FDI). This asymmetry means that even when poorer countries save and accumulate foreign assets, those assets generate little return, while their liabilities remain costly.

Figure 5.7 complements this picture by comparing returns on investments directly. The richest 20% consistently earn more on their assets abroad and pay less on their liabilities. Over the last half-century, global returns on assets have fallen for all, but the decline has been steepest for poorer countries. More importantly, the liability costs have remained high or even increased for the poorer countries. Only the richest 20% have experienced a large decrease in liability costs. The result is a structural advantage for rich countries: they are “charged less” on what they owe.

These patterns are not the accidental outcome of market forces. They stem from policy design and institutional dominance. For instance, regulatory standards such as Basel III increased the demand for “safe” assets, consolidating the role of U.S. Treasuries and European sovereign bonds. Credit rating agencies, largely based in advanced economies, reinforce the perception of safety for rich-country debt and risk for poorer-country debt. Central banks worldwide accumulate reserves in dollars and euros, further entrenching the system. The broader implication is that the richest economies do not simply benefit from privilege; they actively shape and maintain it. By controlling the currencies, rules, and institutions at the center of global finance, they secure a rentier position that channels income from the rest of the world, thereby exacerbating inequality across countries.

Barriers for reducing inequality across countries

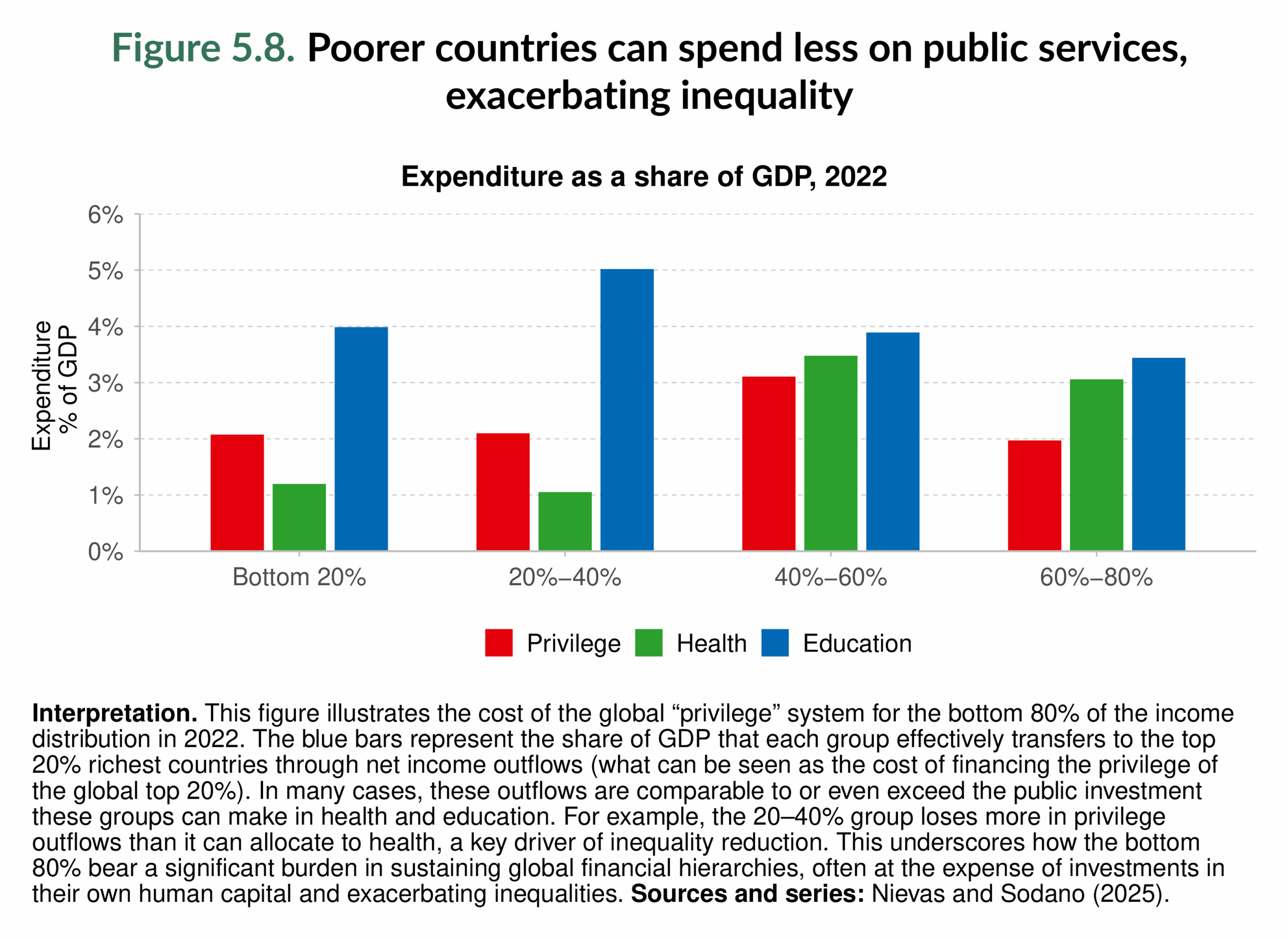

The financial asymmetries documented in this chapter are not only technical imbalances; they translate directly into barriers for development. Figure 5.8 illustrates how poorer countries systematically transfer resources to richer ones, constraining their fiscal capacity and long-term growth prospects.

The bottom 80% of countries devote a significant share of their GDP to net income outflows, which can be seen as the cost of financing the privilege for the top 20%. These outflows, averaging 2–3% of GDP each year, represent resources that could otherwise be invested in schools, hospitals, or infrastructure. The cost is particularly heavy for low-income regions, where financing privilege often demands higher budgets than health expenditure. By contrast, rich countries receive steady inflows, reinforcing their ability to sustain higher living standards.

The implication is stark. The current financial system perpetuates global inequality by design. In many ways, these income transfers function as a modern form of unequal exchange, subtler than colonial extraction, but no less constraining for the development paths of poorer nations.

Need for reforms in the international financial, trade, and monetary systems

Figure 5.9 synthesizes two centuries of evidence on how global asymmetries in trade, finance, and income have been structured (see Nievas and Piketty (2025)). Taken together, its four panels reveal not just fluctuations in balances but enduring patterns of power and privilege in the international financial system.

Panel (a) traces net foreign income balances. It highlights Europe’s remarkable capacity in the 19th century to enjoy positive income flows despite persistent trade deficits. By the eve of World War I, these inflows amounted to about 1.5% of world GDP, an unprecedented record. Panels (b) and (c) explain how this was possible: Europe’s foreign assets, concentrated in colonies, peaked at nearly one-third of world GDP, allowing it to convert deficits in goods and services into surpluses in income.

A striking modern parallel emerges in North America & Oceania. Panel (c) shows the region today holds large negative net foreign assets, while panel (d) confirms a persistent trade deficit. Yet panel (a) reveals that North America & Oceania still records positive net foreign income. The explanation lies in panel (b): excess yield. Like Europe in the colonial era, North America & Oceania, led by the United States, systematically earns higher returns on its assets abroad than it pays on its liabilities. This exorbitant privilege allows the region to live with persistent trade and net foreign asset deficits while continuing to obtain positive net income from the rest of the world.

East Asia, by contrast, follows a more “textbook” path. Its rising creditor position since the 1980s has been built on persistent surpluses in trade, not on privileged yields. This comparison underscores how structural asymmetries and unequal exchange differ in geography but not in essence: colonial Europe relied mainly on extraction and colonial rents; today’s North America & Oceania relies mainly on financial dominance and institutionalized excess yields.

This shows that global imbalances are not corrected by market forces. They are sustained by entrenched hierarchies of finance, trade, and monetary power. Addressing such asymmetries requires systemic reform. A meaningful reform of the global monetary and trade system will require a new mix of rules and institutions. Proposals in Nievas and Piketty (2025) include options such as pegged exchange rates closer to purchasing power parities, expanded use of special drawing rights (SDRs, an international reserve asset created by the International Monetary Fund (IMF)), creation of a global currency, centralized credit and debit systems, and even corrective taxes on excessive surpluses.

The underlying message is clear: global economic relations are shaped less by self-correcting markets than by persistent power asymmetries and structural imbalances. Without bold reforms, the skewed logic of “exorbitant privilege” will continue, locking the Global South into unequal exchange and constraining its development.

Main takeaways

This chapter has shown that what began as the United States’ “exorbitant privilege” has become a structural privilege of the rich world. Advanced economies borrow cheaply, lend profitably, and secure income inflows, while poorer countries face the opposite reality: costly liabilities, low-yield assets, and a persistent outflow of income. These patterns are not the result of market efficiency but of institutional design that places reserve currency issuers and financial centers at the core of the global system.

The evidence demonstrates that this privilege translates into a continuous transfer of resources from poorer to richer countries. Far from narrowing gaps, financial globalization has increased them. This amounts to a modern form of unequal exchange: colonial powers once relied on resource extraction to transform deficits into surpluses; today, advanced economies achieve the same through excess yields.

The burden falls on developing countries, reducing their capacity to invest in education, health, and infrastructure. By constraining human capital formation and fiscal space, the system limits their ability to reduce inequality across countries. Without structural reform, global inequality will persist.

Box 5.1: Exorbitant duty is not so exorbitant

The table illustrates the performance of different country groups during the 2008–2009 global financial crisis. At first glance, the “exorbitant duty” narrative suggests that the richest economies were among those who absorbed the heaviest losses as the cost of providing safe assets to the rest of the world. Yet the evidence tells a different story. The top 20% recorded only modest losses in 2008 (3% of GDP) and quickly recovered with gains in 2009, leaving them essentially unchanged by the crisis. By contrast, the middle 40% of countries faced large and persistent losses in both years, making them the true losers.

This evidence challenges the idea of a heavy “insurance burden” carried by the global rich. Their resilience stems from structural privilege: higher returns, safer liabilities, and the ability to bounce back swiftly. The so-called duty is episodic and modest, while the exorbitant privilege is enduring.

1 BRICS is an acronym referring to a group of major emerging economies: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.