Climate change is advancing at a pace that far exceeds early projections. By 2025, the remaining carbon budget compatible with limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels is nearly exhausted (Forster et al. (2025)). The cumulative consequences of extreme climate events are becoming increasingly visible, affecting livelihoods, infrastructure, and economic stability worldwide.

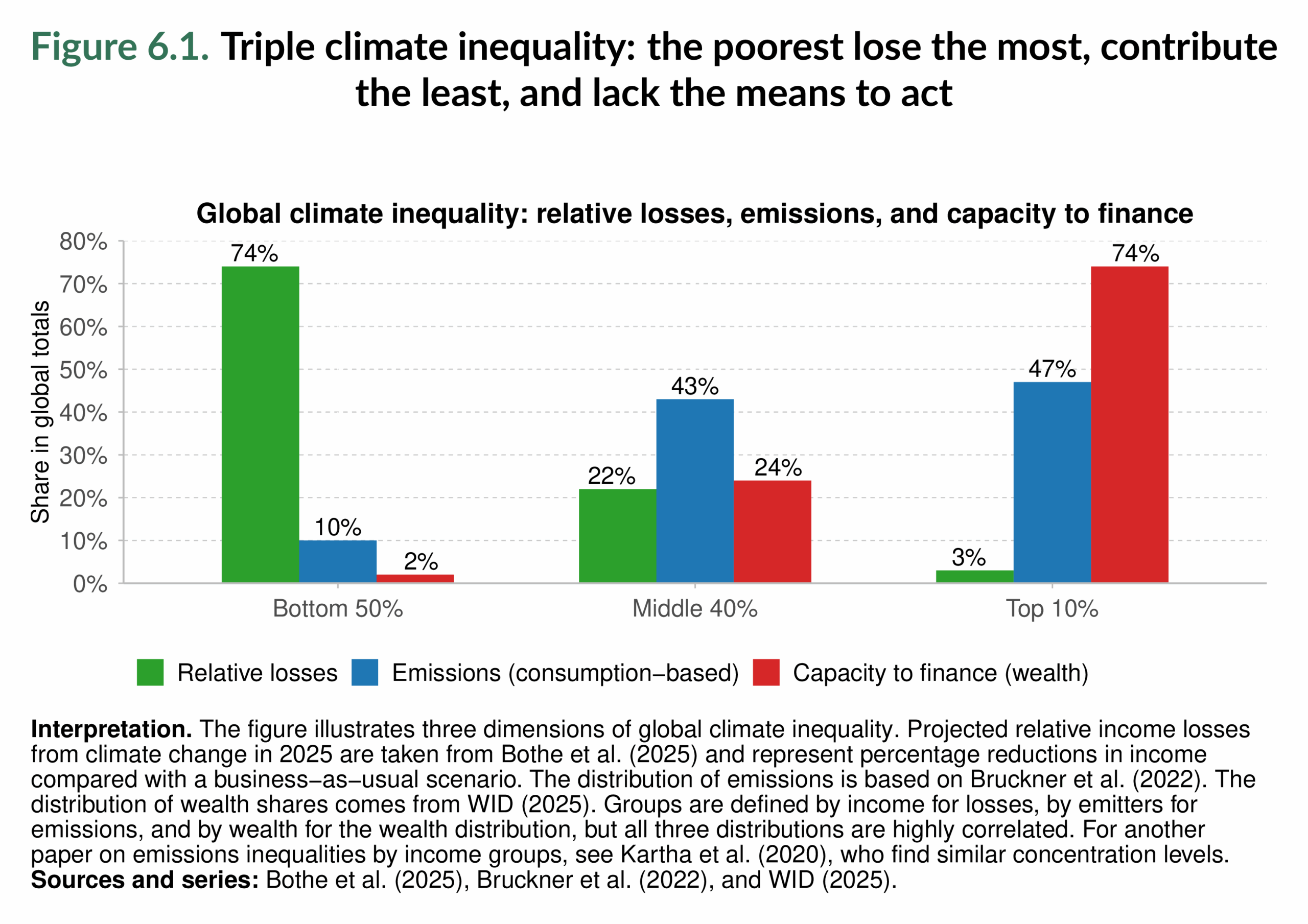

As the Climate Inequality Report 20251 shows, the climate crisis is unfolding in a world marked by profound economic inequality and highly concentrated wealth. These two dynamics are deeply intertwined. Wealthy individuals not only contribute disproportionately to global emissions but are also better shielded from the damages of climate shocks. They hold the financial, corporate, and political power to shape the pace and direction of the climate transition (see Figure 6.1).

Conversely, climate change and the policies designed to mitigate it are transforming how wealth is created, distributed, and preserved. The intensification of physical climate risks, the repricing of assets, and the reallocation of investments toward green sectors will have far-reaching implications for the global distribution of private and public wealth.

This chapter examines how wealth fuels climate change and how, in turn, climate change reshapes wealth inequality. It introduces an ownership-based perspective on emissions that reveals how capital ownership concentrates the power to pollute, and the responsibility for climate damages, at the top of the wealth distribution. It then explores the economic and social channels through which climate change and climate policies alter the distribution of private and public assets.

The climate crisis is also a capital crisis. To effectively address it, we must not only reduce emissions but also rethink how ownership, investment, and wealth are governed in the transition to a sustainable economy.

The carbon footprint of capital

The unequal contribution of rich and poor countries to climate change is one of the most striking manifestations of global inequality. At the international level, the average carbon footprint of the top 10% income group in the United States—measured by emissions linked to their consumption—is more than forty times greater than that of the top 10% in Nigeria, and over 500 times greater than that of Nigeria’s bottom 10%. At the global level, a person in the global top 1% income group emits, on average, around seventy-five times more carbon per year than someone in the bottom 50% (Bruckner et al. (2022)).

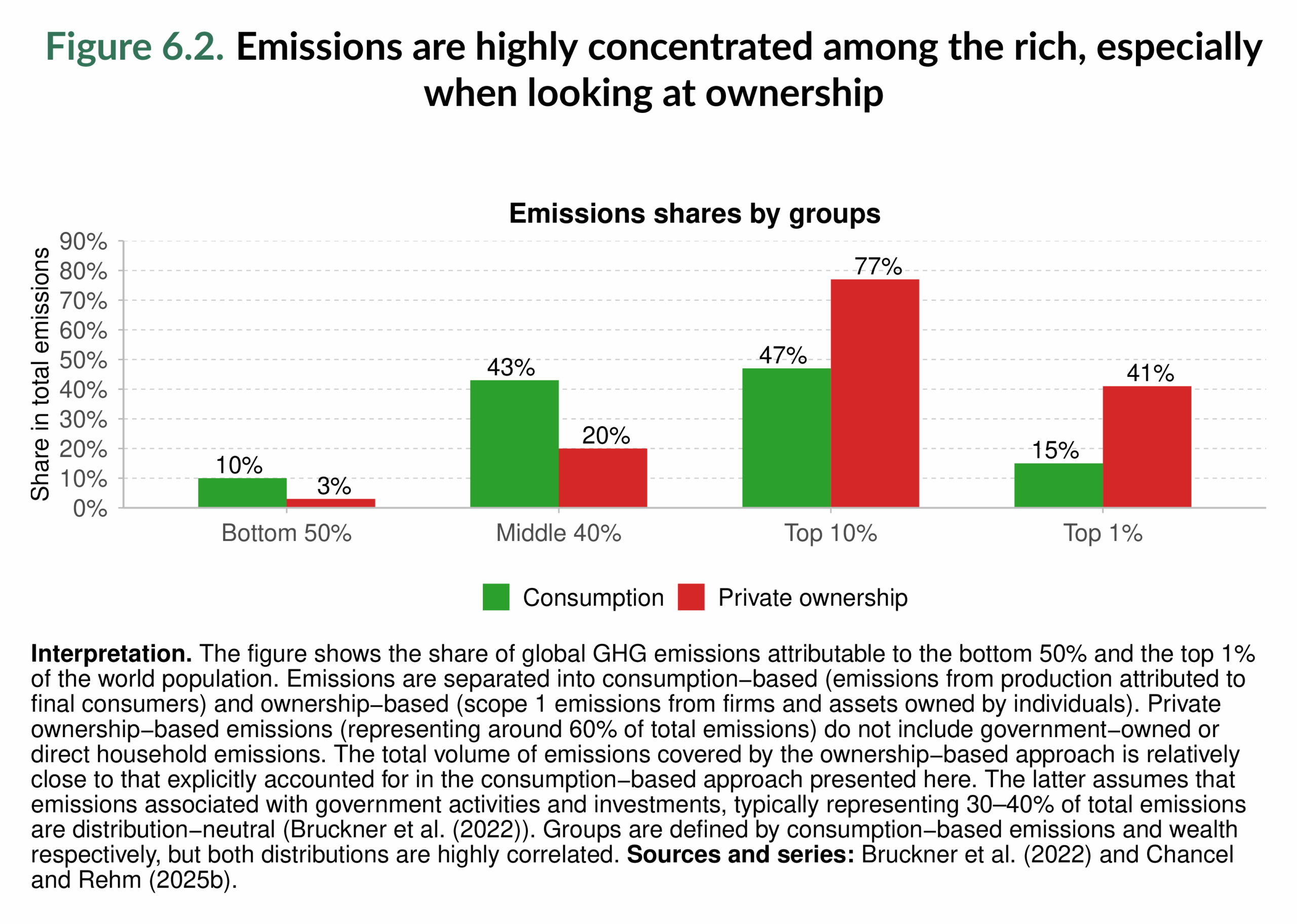

Most emission estimates traditionally attribute greenhouse gases to the final consumers of goods and services. This “consumption-based” approach highlights differences in lifestyle and consumption patterns. However, it overlooks another critical dimension of responsibility: capital ownership.

While many consumers have limited ability to alter their consumption, due to constrained budgets, a lack of information, or limited access to alternatives, owners of productive assets actively decide how and where resources are invested. They directly benefit from the profits generated by emission-intensive industries. An ownership-based approach, therefore, assigns emissions from production to those who own the corresponding capital stock.

Under this framework, an individual owning 50% of a company’s equity is attributed 50% of that firm’s emissions, whether directly or via intermediaries such as investment funds. Importantly, this approach does not allocate emissions generated directly by households, such as those from residential heating or private vehicle use, nor those linked to government consumption or capital ownership. The ownership-based approach discussed in this chapter only accounts for nearly 60% of global emissions that can be directly attributed to private capital ownership by individuals (Chancel and Rehm (2025a)).

Accounting for emissions through this ownership lens reveals a high degree of concentration. In France, Germany, and the United States, the carbon footprint of the wealthiest 10% is three to five times higher when private ownership–based emissions are included. In the United States, the top 10% accounts for 24% of consumption-based emissions but 72% of ownership-based emissions. The share of the top 1% rises from 6% (consumption-based) to nearly 43% (ownership-based).

At the global scale, the contrast is even sharper. The top 1% accounts for 41% of all greenhouse gas emissions under ownership-based accounting, compared with 15% under the consumption approach. Conversely, the contribution of the bottom 50% drops from 10% to 3% (Figure 6.2). In other words, the average individual in the top 1% emits more than twenty-five times as much carbon as the global average citizen. Their share of emissions even exceeds their share of global wealth—estimated at 36% in 2022 (Chancel and Rehm (2025a)).

The extreme concentration of private ownership–based emissions stems from both the amount of wealth owned and the investment choices made. Wealthy individuals not only hold larger asset portfolios but also allocate them disproportionately toward high-carbon sectors.

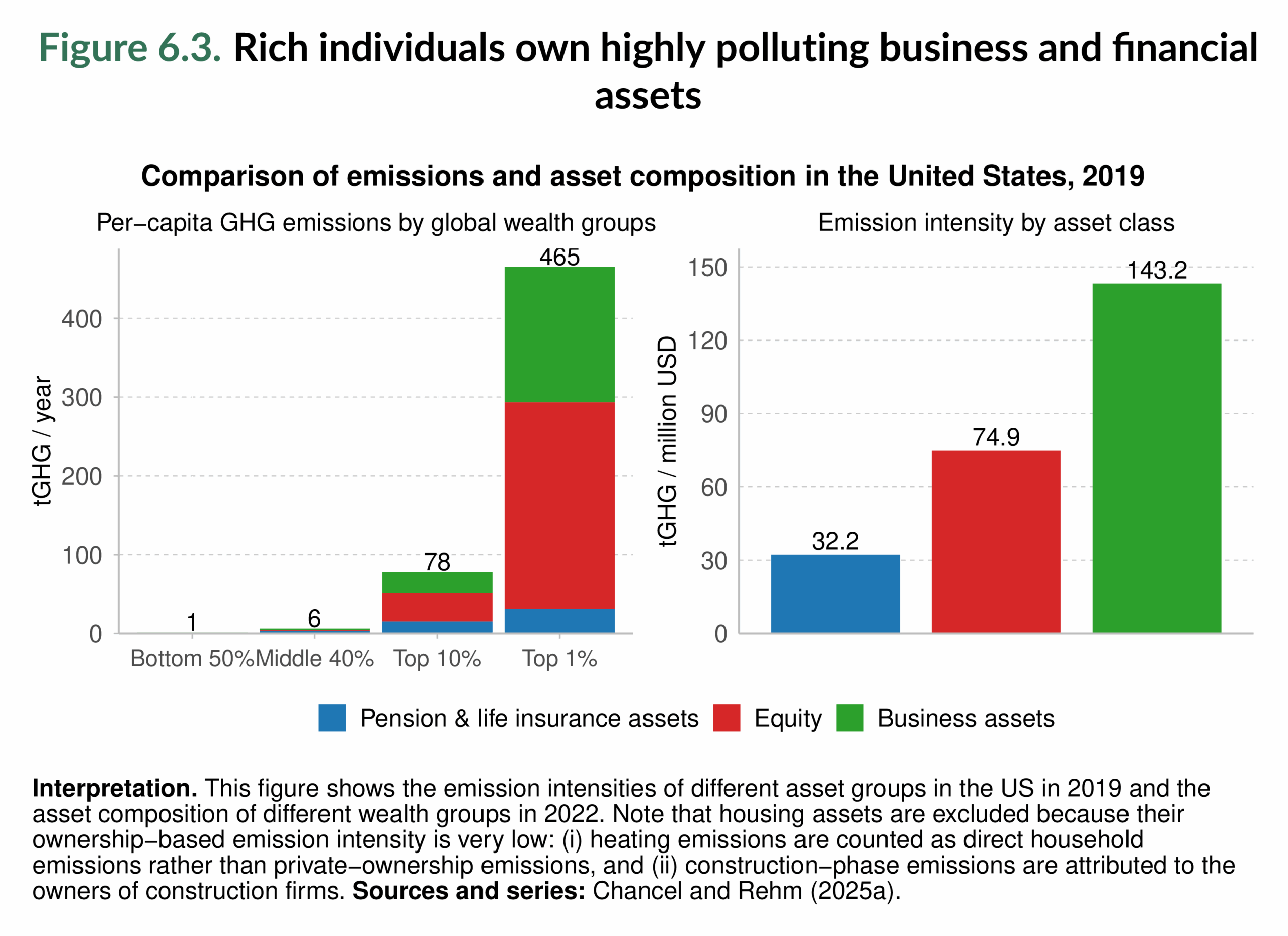

As shown in Figure 6.3, every $1 million invested in business assets in the United States corresponds to roughly 143 tonnes of carbon emissions, compared with 75 tonnes for equities (Chancel and Rehm (2025a)). Similar patterns emerge in France and Germany.

The global top 10% allocates about half of their wealth to such carbon-intensive holdings, often seeking higher-risk, higher-return investments that coincide with higher emissions. Hsu, Li, and Tsou (2022) find that high-emission companies yield, on average, 4.4 percentage points more in annual excess returns than low-emission peers—an implicit “pollution premium” that further incentivizes carbon-heavy investments.

From this ownership perspective, the nature of emissions changes across the wealth distribution. For low- and middle-income groups, nearly all emissions are linked to essential consumption—transportation, heating, or electricity. For the top 10%, and especially for the top 1%, emissions from capital ownership dominate, accounting for 75–95% of their total footprint in France, Germany, and the United States. This also means that the wealthiest have a far greater capacity to reduce emissions without compromising their living standards.

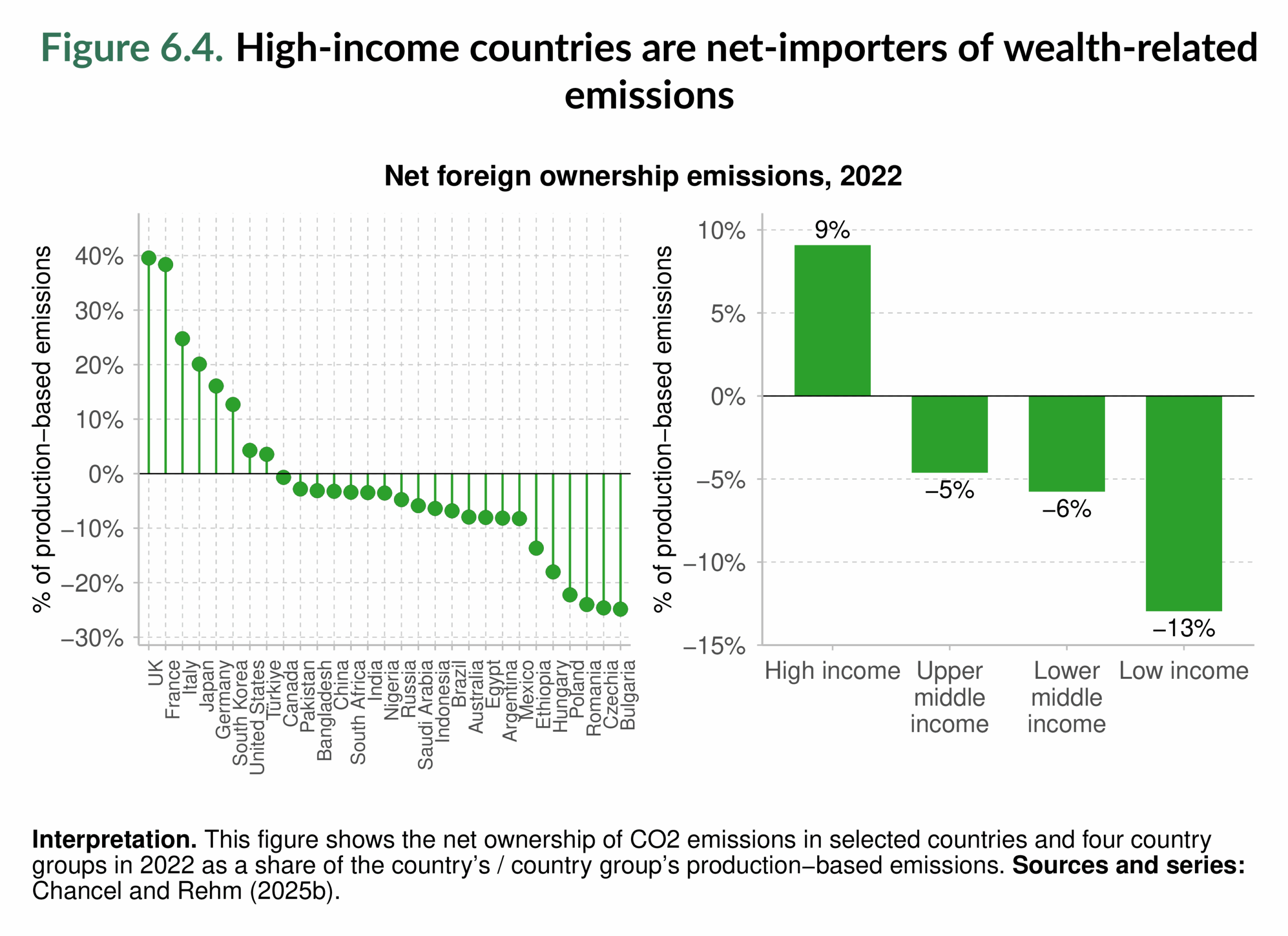

Taking a global view, net ownership positions reveal how investors in high-income countries profit from pollution abroad. Figure 6.4 shows that major European economies, Japan, and South Korea exhibit large positive net ownership-emission positions. In France, adjusting for international investment raises national emissions by 36%, reflecting the fact that French investors own polluting production facilities abroad whose emissions exceed those generated domestically by foreign-owned firms.

By contrast, many middle- and low-income countries show negative net positions: part of the emissions from their domestic production is ultimately attributable to foreign investors in richer countries.

These patterns point to a crucial implication: climate regulations and taxation should take asset ownership into account. Evidently, stronger regulations on high-carbon investments are necessary. In addition, a carbon tax on wealth, based on the carbon content of owned assets or of investments, would arguably be significantly more progressive than a consumption-based levy. It would ensure that those who profit most from carbon-intensive activities, often across borders, contribute their fair share to the transition to a greener economy.

Decarbonizing at home, burning fuels abroad?

By focusing on investment in carbon-intensive activities, we can also bring to light current global contradictions. Even as many countries pledge to decarbonize domestically, capital continues to flow into fossil-fuel extraction abroad. This investment pattern is not accidental: it reflects the concentration of financial power among wealthy investors and corporations that operate across borders.

In 2025, global capital flowing into fossil fuel projects still amounts to approximately USD 1.1 trillion. "Clean" energy, including renewables, electricity grids, storage, and low- emission technologies, at the same time receives USD 2.2 trillion, or roughly twice as much as fossil fuels. Government policies have reinforced these trends. In response to the recent energy price spikes, fossil-fuel consumer subsidies tripled between 2020 and 2022. The environmental consequences of these investments are staggering. Fossil-fuel projects destroy ecosystems, pollute water and air, and displace communities (Shamoon et al. (2022)). More importantly, they lock in future emissions: most facilities are designed to operate for twenty to forty years, delaying the transition to clean energy.

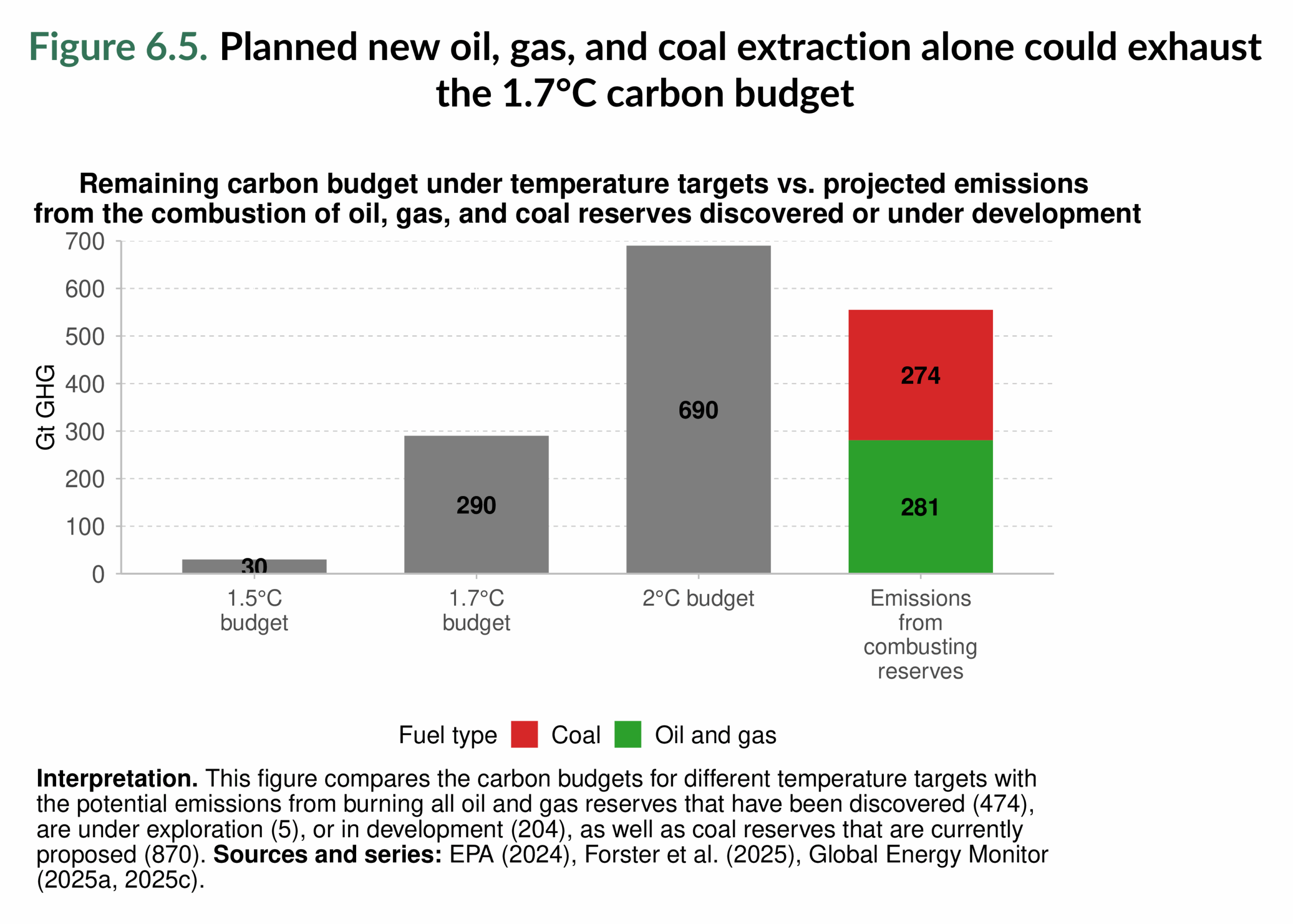

Figure 6.5 illustrates the scale of the challenge. The potential emissions from fossil-fuel reserves currently in development or exploration are, by themselves, sufficient to deplete the carbon budget that would limit warming to 1.7°C . These emissions would come in addition to those from existing extraction sites.

Despite this, fossil-fuel projects remain financially attractive. As the International Energy Agency (2025) notes, investment in new oil, gas, and coal projects continues to rise, driven by short-term returns that overshadow long-term planetary costs.

Climate change already shapes the distribution of private and public wealth

The economic impacts of climate change are deeply unequal. Both between and within countries, poorer households and nations bear the heaviest burden. Global warming and associated extreme events disproportionately affect low-income populations due to higher exposure, greater vulnerability, and more limited capacity to adapt (Alizadeh et al. (2022); Burke, Hsiang, and Miguel (2015); Kalkuhl and Wenz (2020)).

Between 1961 and 2010, anthropogenic climate change is estimated to have widened the income gap between the world’s richest and poorest countries by roughly 25% compared with a scenario without climate change (Diffenbaugh and Burke (2019)). Within countries, the poorest households are more likely to live in areas exposed to environmental hazards and are less protected from their effects (Gilli et al. (2024); Palagi et al. (2022)).

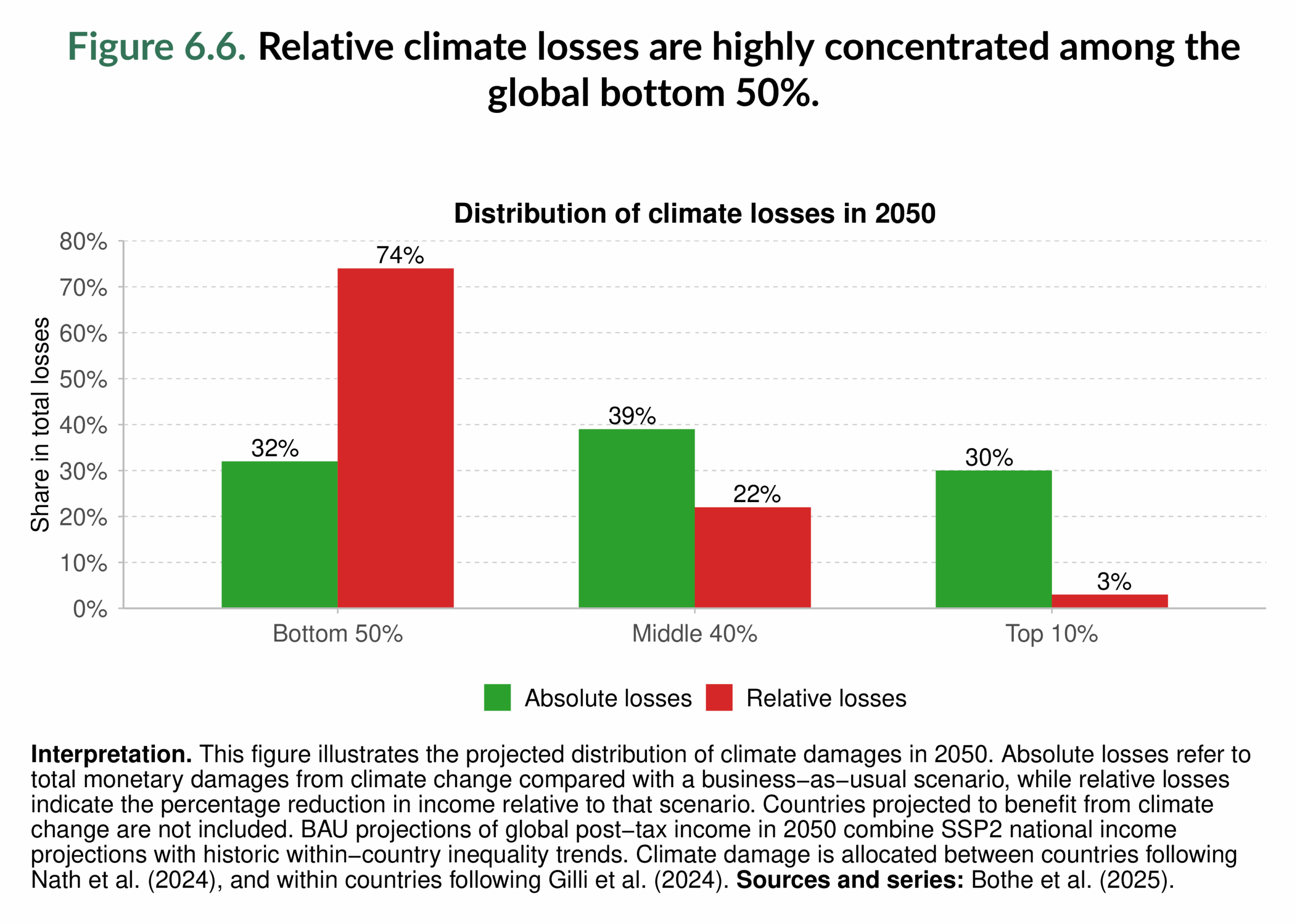

At the global level, the bottom 50% of the population could bear up to 75% of total relative climate damages by 2050 (Bothe et al. (2025)). While absolute losses are higher in richer households, simply because they earn and own more, the relative impact on income and assets is vastly greater for poorer groups (Figure 6.6). A single flood, drought, or storm can erase years of accumulated savings, while for the wealthy, such shocks typically represent temporary financial setbacks.

Beyond income, the climate crisis affects nearly every form of wealth. Physical assets, such as housing, land, and infrastructure, are vulnerable to floods, storms, fires, and heat. Market evidence already shows declining property values in high-risk areas (Baldauf, Garlappi, and Yannelis (2020); Bosker et al. (2019)). Between 2020 and 2023, climate-related disasters caused an estimated €162 billion in asset losses across the European Union, roughly equivalent to the entire EU annual budget (EEA (2024)).

In developing countries, the impacts are far more devastating. The 2022 Pakistan floods caused damages worth about $40 billion (Mishra (2025)). Overall, 89% of the world’s flood-exposed population lives in low- and middle-income countries (Rentschler, Salhab, and Jafino (2022)).

Wealthier households are not immune, but they are better protected. They can diversify assets, relocate, or rely on insurance and public compensation. In contrast, poorer households hold most of their wealth in housing and deposits, making them highly vulnerable to physical loss.

Insurance and public safety nets could mitigate these risks, but coverage remains highly uneven. Three in four people in low-income countries lack any form of social protection (World Bank (2025)). Even in high-income economies, only about 35% of climate-related losses are insured (EEA (2024)).

Climate change also exerts growing pressure on public wealth. At the municipal level, recurrent disasters erode property tax bases. In Florida, for instance, more than half of local governments are projected to be affected by sea-level rise by the end of the century, with 30% of their revenues derived from properties at risk of chronic flooding (Shi et al. (2023)).

National governments face rising fiscal pressures from reconstruction spending, emergency aid, and social protection. In the Caribbean, hurricanes have repeatedly driven spikes in public debt, while in the Middle East & North Africa, higher temperatures are associated with deteriorating fiscal balances (Giovanis and Ozdamar (2022); Mejia (2014)).

Financial markets increasingly price climate risk into sovereign borrowing costs, making it more expensive for vulnerable countries to access credit. This dynamic can create a vicious cycle: the countries most in need of financing for adaptation and mitigation face the highest interest rates (Cappiello et al. (2025)).

Over time, the erosion of both private and public wealth may further constrain governments’ ability to invest in climate resilience and public goods—deepening the inequality gap between those with the means to adapt and those without.

Climate policy and the future distribution of wealth

The coming decades will not only test the world’s capacity to reduce emissions, they will also redefine how wealth is distributed. Climate policy design will determine whether the net-zero transition becomes an opportunity to reduce inequality or a source of new disparities.

Market-based instruments, such as carbon taxes, can be regressive if poorly designed. In high-income countries, evidence shows that low-income households spend a larger share of their income on carbon-intensive goods, making them more vulnerable to price increases (Ohlendorf et al. (2021)). Compensation mechanisms, such as cash transfers or free energy quotas, are therefore crucial to ensure fairness.

Another major challenge lies in asset stranding. The accelerated phase-out of high-carbon infrastructure and industries implies that some assets will lose much of their value. Under a 1.5°C scenario, the upstream oil and gas sector alone could lose between $7 and 12 trillion in value (Jakob and Semieniuk (2023)). While most stranded assets are owned by wealthy investors in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD ) countries, these losses represent only about 0.4% of their net worth (Semieniuk et al. (2022)), a tiny dent in their total wealth.

Public wealth, however, is more directly at risk. Governments own roughly one-third of the assets exposed to stranding, particularly in non-OECD countries (Semieniuk et al. (2022)). If public entities or development banks absorb these losses, fiscal space could shrink dramatically. Moreover, climate-related financial instability could lead to public bailouts, effectively transferring private losses onto taxpayers (Lamperti et al. (2019)).

Governments also face litigation risks through investor–state dispute settlements. If fossil-fuel projects protected by international treaties are canceled to meet climate targets, affected investors can sue for compensation. Potential claims from such disputes could reach $60–230 billion (Tienhaara et al. (2022)).

At the same time, the financing and ownership structure of green investments will shape tomorrow’s wealth distribution. The global transition to net zero will require an estimated $266 trillion in cumulative investment by 2050 (Buchner et al. (2023))—a fivefold increase from current levels.

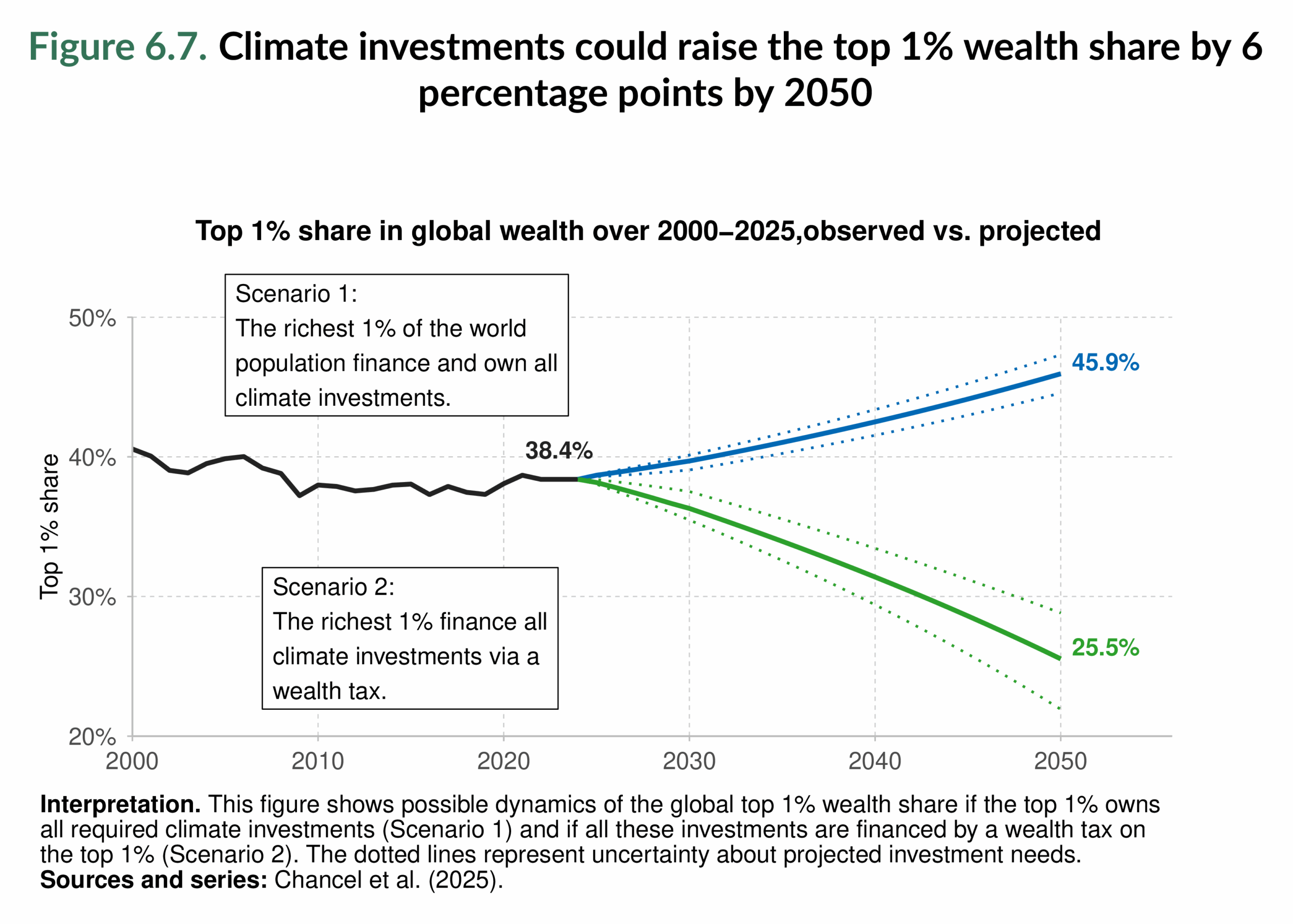

Figure 6.7 illustrates two possible scenarios: if the richest 1% finance and own all new climate investments, their global wealth share could rise from 38% today to 46% by 2050. Conversely, if these investments are publicly financed and collectively owned, the top 1% share could decline to 26%.

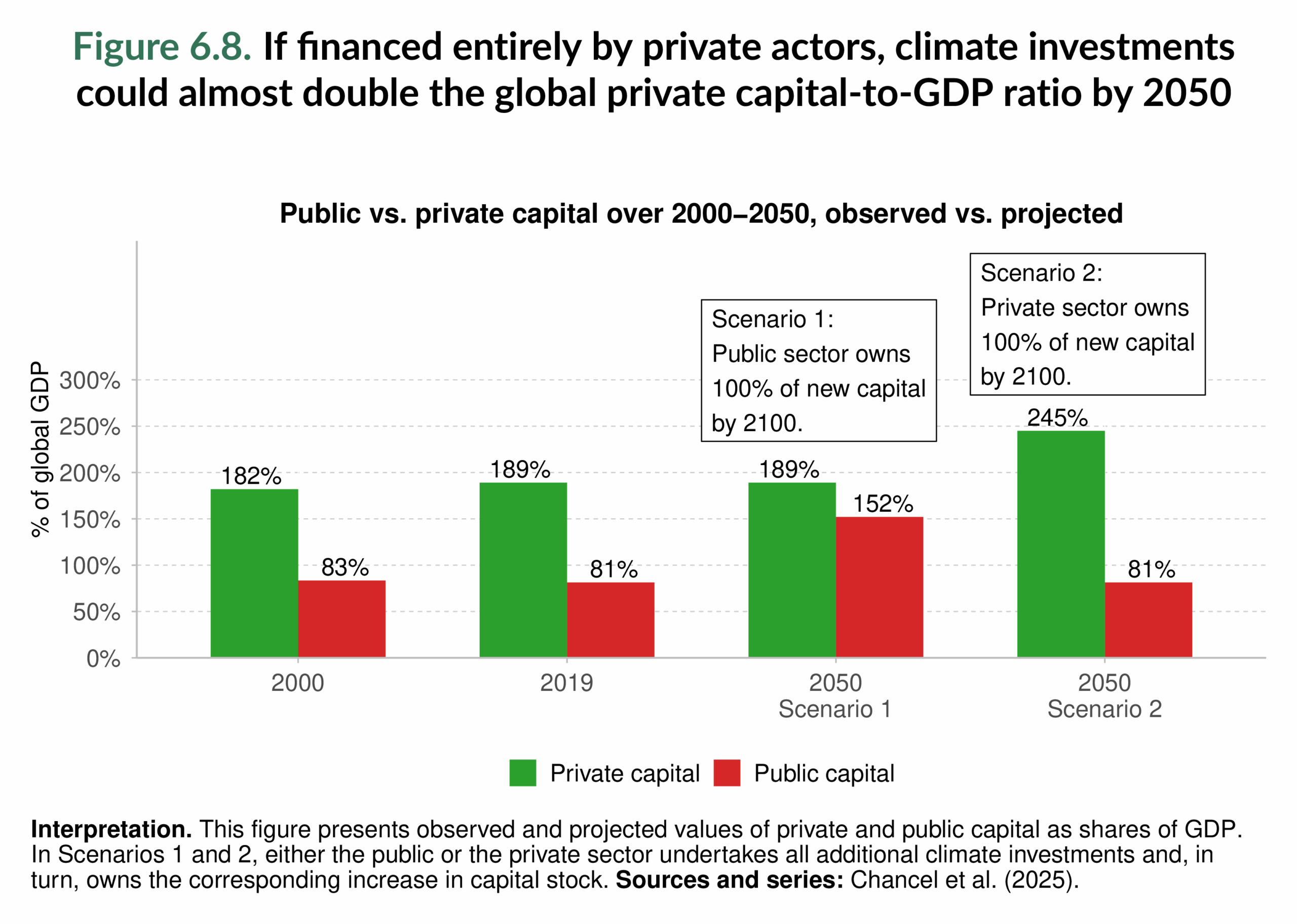

The implications for public capital are equally significant. If the public sector undertakes and owns all required climate investments, public capital could rise from around 80% of GDP in 2019 to over 150% by 2050 (Figure 6.8). If private investors capture these opportunities instead, the private capital stock could climb to 245% of GDP , while public capital remains stagnant.

The distributional consequences of the green transition therefore depend not only on climate ambition but also on who owns the transition. Public policies that promote equitable financing, transparent ownership, and redistribution of green returns are essential to ensure that the path toward sustainability does not widen global wealth divides.

Main takeaways

Wealth and climate change are bound together by powerful feedback loops. The wealthiest individuals not only consume more but also own and profit from the assets that generate the majority of greenhouse gas emissions. When emissions are attributed through ownership rather than consumption, inequality appears even starker: the global top 1% account for over 40% of emissions, while the bottom half contribute almost none.

This concentration of both economic and environmental power shapes how societies confront the climate crisis. Capital continues to flow into fossil-fuel production, locking in decades of future emissions, even as wealthy countries pledge to decarbonize. At the same time, the poorest populations, those least responsible, face the heaviest relative losses from climate impacts.

Climate change also redistributes wealth. It erodes private and public assets through physical damages, rising debt, and lower fiscal capacity, while green investments and asset repricing can further widen or reduce inequality, depending on who owns and determines the rules of the net-zero transition. A privately financed net-zero pathway would almost certainly reinforce global concentrations of wealth, whereas public investment and progressive taxation could transform the transition into a lever for equity.

The findings of this chapter point to a central conclusion: the climate crisis is a capital crisis. Effective climate action demands of us that we rethink investment regulations, ownership structures, and the taxation of capital. Enlightened policies such as restrictions on new fossil-fuel investments, progressive wealth taxes imposing an effective carbon penalty, and the expansion of public ownership of climate assets can accelerate the transition and help to reduce wealth inequalities. If we fail to design climate policies that tackle the distribution of capital and ownership patterns, we will miss a crucial opportunity to address another deeply entrenched form of inequality.

1 See Chancel and Mohren (2025).