Despite major social and economic transformations over the past two centuries, gender inequality remains a defining feature of the global economy. Women today are more educated, more active in the labor market, and more visible in positions of leadership than ever before. Yet, when we examine how work hours and income are divided between men and women, a striking reality emerges: the world is still a long way from achieving gender parity.

At the global level, women contribute significantly to both paid and unpaid work, but their economic rewards remain much smaller. They are more likely to work longer hours when both market and household labor are counted, yet they earn less, own less, and occupy fewer formal jobs. Across every region, women’s shares of labor income lag behind men’s, and progress in narrowing these gaps has been slow. Even where gains have been made in education or employment participation, they have not translated into equal pay or equal access to opportunities.

Figure 4.1 helps place this imbalance in perspective. It shows that women still suffer gender inequalities across several key dimensions. Women contribute a majority of total working hours worldwide, once unpaid domestic work is included, yet they only earn around one-third of aggregated labor income. Focusing on economic work, employment rates lag significantly behind those of men, with women much less likely to hold a paid job, and when employed, they earn substantially less per hour. Even in education, where female high school enrollment has increased dramatically, parity has not been fully achieved at the global level. These figures reveal not only that gender inequality persists, but that its scope should be apprehended in all its complexity by studying its social, educational, and economic dimensions. Gender inequality is persistent and structural, not just a declining historical feature of the global economy.

Humanity works fewer hours, but the benefits are unequal across genders

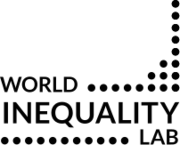

One of the most striking long-run transformations in the global economy is the decline in working hours. Two centuries ago, the typical worker spent more than sixty hours per week in market employment. Today, average hours have fallen dramatically, with all regions working around thirty to forty-five hours per week. This reduction reflects profound structural changes: industrialization, rising productivity (right-hand panel of Figure 4.2), the spread of labor rights and collective action, as well as, in some contexts, institutional change and deliberate policies aimed at shortening the working week. As the left-hand panel of Figure 4.2 illustrates, Europe today records the lowest average hours worldwide, often below thirty per week, while South & Southeast Asia remain closer to forty-five. The overall picture is one of a world population that, on average, spends less time in formal work than in the past.

Yet this aggregate progress conceals persistent gender divides. Figure 4.3 highlights that women continue to work longer hours overall than men once unpaid domestic labor is included. Across the world, women devote more hours to household responsibilities. These hours are rarely compensated or formally recognized, but they represent a substantial portion of total labor time and contribute directly to social welfare. The result is a paradox: men appear to work longer when only market hours are considered, but women consistently surpass them in total working hours once unpaid activities are taken into account.

This imbalance carries deep implications. First, it can limit women’s opportunities in the labor market, as time spent on unpaid work constrains the hours available for paid work, training, or career advancement . This, together with fewer paid jobs available for women, gender discrimination, and cultural norms, increases gender inequality. Second, it reinforces the wage gap: women not only work more hours in total, but they also earn less for the paid portion of their labor. Ultimately, it highlights how gender inequality extends beyond wages and employment statistics to the organization of daily life. Working time itself is unequally distributed, with women bearing the heavier load. Their labor is rendered invisible by the non-inclusion of domestic and care work in national accounts.

The long-run decline in global working hours is therefore a story of uneven gains. Humanity may be working fewer hours overall, but men have benefited most from the reductions in formal work, while women’s total workload remains high. This uneven distribution of time is one of the clearest demonstrations that progress in labor conditions has not automatically translated into gender parity.

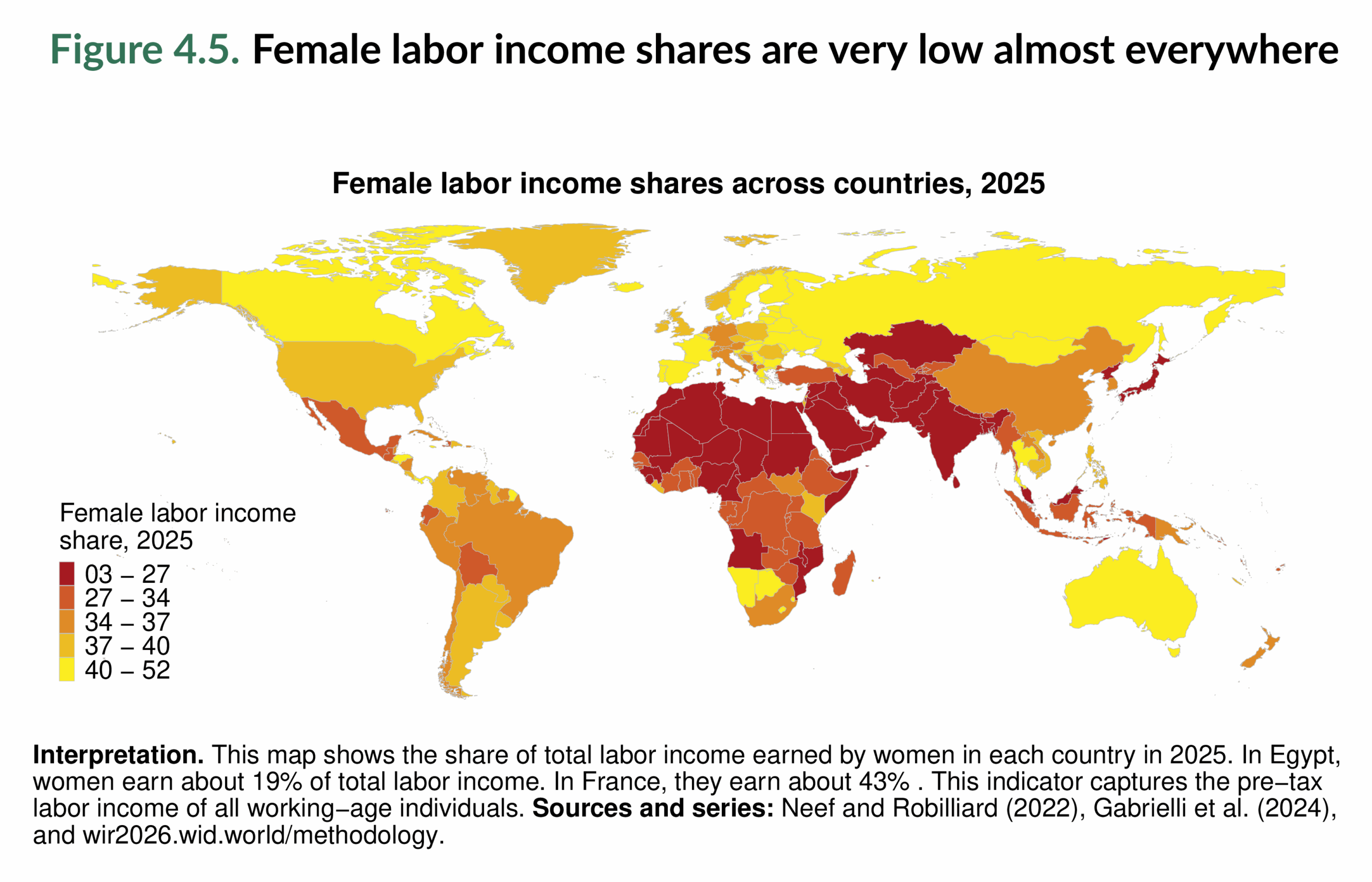

In some regions, there have been improvements, but female labor income shares remain well below equality (see Figure 4.4). No region in the world has reached a 50–50 balance between men and women, and the gaps are especially pronounced in South Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Africa, where women capture less than a quarter of all labor income (see Figure 4.5).

Globally, women earn just about one-third of total labor income today. By contrast, Europe, North America & Oceania, and Russia & Central Asia record the highest female labor income shares, reaching around 40%, but this is still lower than the perfect parity case, which would mean a labor income share of 50%. These regions have seen sustained improvements, driven by higher female participation in the labor market, stronger legal protections, and expanding welfare systems. Figure 4.4 and Figure 4.5 show that the gender gap in labor income is both large and persistent. Women’s income share has risen, but only slowly. Gender inequality in labor earnings remains a structural feature of the global economy.

Women work more hours everywhere. The gender gap is larger than we previously thought

If women’s share of labor income is persistently lower, one might assume that they also work fewer hours. The opposite is true. Figure 4.6 and Figure 4.7 reveal that women, on average, work more hours than men worldwide once unpaid domestic work is included. The gender gap in total working time is not only substantial but also larger than what conventional measures have long suggested.

Traditional labor statistics have tended to focus narrowly on hours of paid work, thereby underestimating women’s contributions. When only market work is counted, men often appear to work longer, particularly in regions with high levels of formal male employment. But when unpaid household activities are properly measured, the picture changes radically: women consistently outwork men in total hours. This reality has been documented by recent research1.

Figure 4.6 illustrates this at the European level, providing a clear example of how the calculation works. It compares women’s share of working time when only paid labor is considered (the conventional measure) with their share once unpaid domestic and care work is included (the real measure). The gap widens substantially (from 8% to 43%) when all forms of labor are accounted for, revealing how much conventional statistics underestimate women’s contributions.

Figure 4.7 extends this comparison to the global scale. Instead of focusing on global averages, the regional decomposition contrasts the conventional and real gender gaps across major world regions today. The results are striking: in every region, the inclusion of domestic work significantly raises women’s share of total labor time, but also highlights that women systematically work more than men everywhere. This regional comparison shows that the underestimation of women’s work is not limited to Europe. Its historical evolution has led to different regional trends and different amplitudes of the gender gap. However, the gender gap in labor income is an undeniable global phenomenon that persists in the present.

Women are employed less than men

Beyond differences in hours worked, a fundamental gap remains in access to employment itself. Figure 4.8 shows that, across all world regions, women are less likely than men to hold a job in the labor market. While patterns vary across regions, the global pattern is clear: women’s employment rates trail men’s by a wide margin.

The employment gap is particularly large in South & Southeast Asia and the Middle East & North Africa. In these regions, around one in three women of working age are employed in the economic market, compared with more than two-thirds of men. By contrast, Europe, Russia & Central Asia, and North America & Oceania display higher female employment rates, yet even here the gap is significant.

This divide cannot be explained by individual choice alone. Structural barriers play a central role. Access to affordable childcare, transportation, and family leave policies strongly influence women’s ability to enter and remain in the labor force. In countries where such support is weak, women are more likely to withdraw from paid employment, especially after childbirth. Discrimination in hiring and promotion also reduces opportunities, particularly in higher-paying sectors.

The persistence of employment gaps has ripple effects across the economy. Lower female participation reduces women’s labor income shares (as seen in Figure 4.4 and Figure 4.5) and constrains overall economic potential. Studies consistently show that economies with higher female labor force participation experience stronger growth and a more equitable distribution of income. Yet, despite these benefits, progress has been slow and uneven, suggesting that employment inequalities are deeply embedded in economic and social structures.

Employed women earn less than employed men

Even when women overcome barriers to employment, they face another persistent challenge: lower pay. Figure 4.9 highlights the global gender pay gap, showing that employed women consistently earn less than employed men across all regions. This gap exists at every income level, in both highand low-income regions, with a few gains during recent decades in Latin America, North America & Oceania, Europe, and Russia & Central Asia.

The gap is still present despite decades of anti-discrimination laws and advocacy. The magnitude varies by region: the gap is widest in Sub-Saharan Africa and South & Southeast Asia. Employed women earn about 75% of what employed men earn in North America & Oceania, Europe, Russia & Central Asia, and East Asia. The persistence of this divide underscores that it is not simply a legacy of the past, but a structural feature of contemporary labor markets.

Several factors contribute to the wage gap. Occupational segregation plays a major role: women are overrepresented in sectors that pay less, such as education, healthcare, and domestic services, and underrepresented in higher-paying fields like finance, engineering, and technology. Within firms, women are less likely to occupy senior positions and more likely to be hired in part-time or precarious roles, which reduces

average earnings. The economic consequences are far-reaching. Lower pay compounds over time, leading to smaller savings, weaker pensions, and reduced wealth accumulation. Women not only earn less during their working years but can also accumulate lower wealth, reinforcing inequalities across generations. The gender pay gap is, therefore, more than a matter of fairness in wages. It reflects how societies value different kinds of work and how power is distributed in the labor market.

The role of education in improving the gender gap

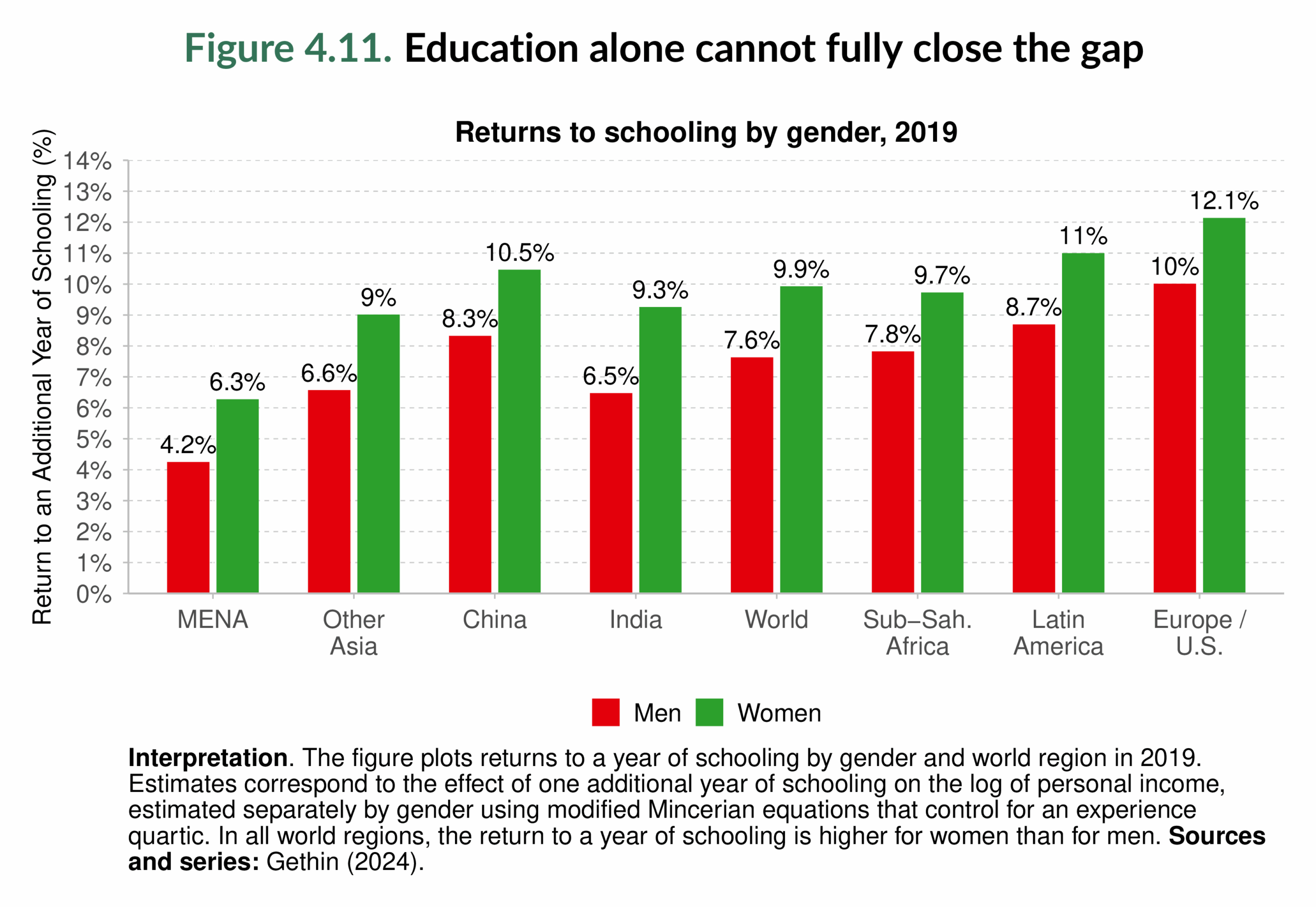

Education is often viewed as the most powerful equalizer. Expanding access to schooling has indeed transformed women’s lives worldwide, enabling them to enter the labor market in greater numbers and to aspire to careers that were once out of reach. Yet Figure 4.10 and Figure 4.11 reveal that while education has narrowed some gender divides, it has not been sufficient to eliminate them.

Figure 4.10 shows that women’s educational participation has improved dramatically in this century. In low- and middle-income economies, the school enrollment gender gap has decreased in the last twenty-five years from 85% to 98%, reaching almost full parity. In high-income countries, young women now outnumber men in secondary education enrollment. These advances have been crucial in raising female employment and income levels, as education increases opportunities to access formal jobs and higher wages.

However, Figure 4.11 reminds us that education alone cannot fully close the gap. Even when women achieve the same or higher levels of schooling and income returns on schooling, their labor income share remains lower than men’s. The link between education and equality is therefore partial and mediated by broader labor market structures. High levels of female education have not translated into equal employment or pay, due to persistent cultural and institutional barriers.

The lesson is clear. Education is necessary for gender equality but not sufficient on its own. Without policies that address workplace discrimination, provide childcare support, and promote equal opportunities, the returns on education for women will remain systematically lower than for men.

Main takeaways

Gender inequality remains a defining and persistent feature of the global economy. Women today are more educated, more active in the labor market, and more present in leadership positions, yet their economic standing continues to lag behind men’s.

Women work longer hours than men once unpaid domestic and care work is included, but they capture only about one-third of total labor income. This paradox reflects how aggregate progress has been unevenly distributed. Employment and pay gaps reinforce this imbalance. Women are less likely to hold paid jobs in every region, and when employed, they consistently earn less than men. This has long-term effects on savings, pensions, and wealth accumulation, increasing inequality.

Education has narrowed some gaps, with women achieving near parity in high-school enrollment, but schooling alone has not eliminated inequalities. Historical evidence shows that progress is slow and uneven. The lesson is clear: gender parity is by no means a guaranteed result of narrowing gender inequality. For genuine gender parity to be achieved requires sustained institutional change, supportive policies, and recognition of the invisible labor that women continue to perform disproportionately to men.

1 See Andreescu et al. (2025).