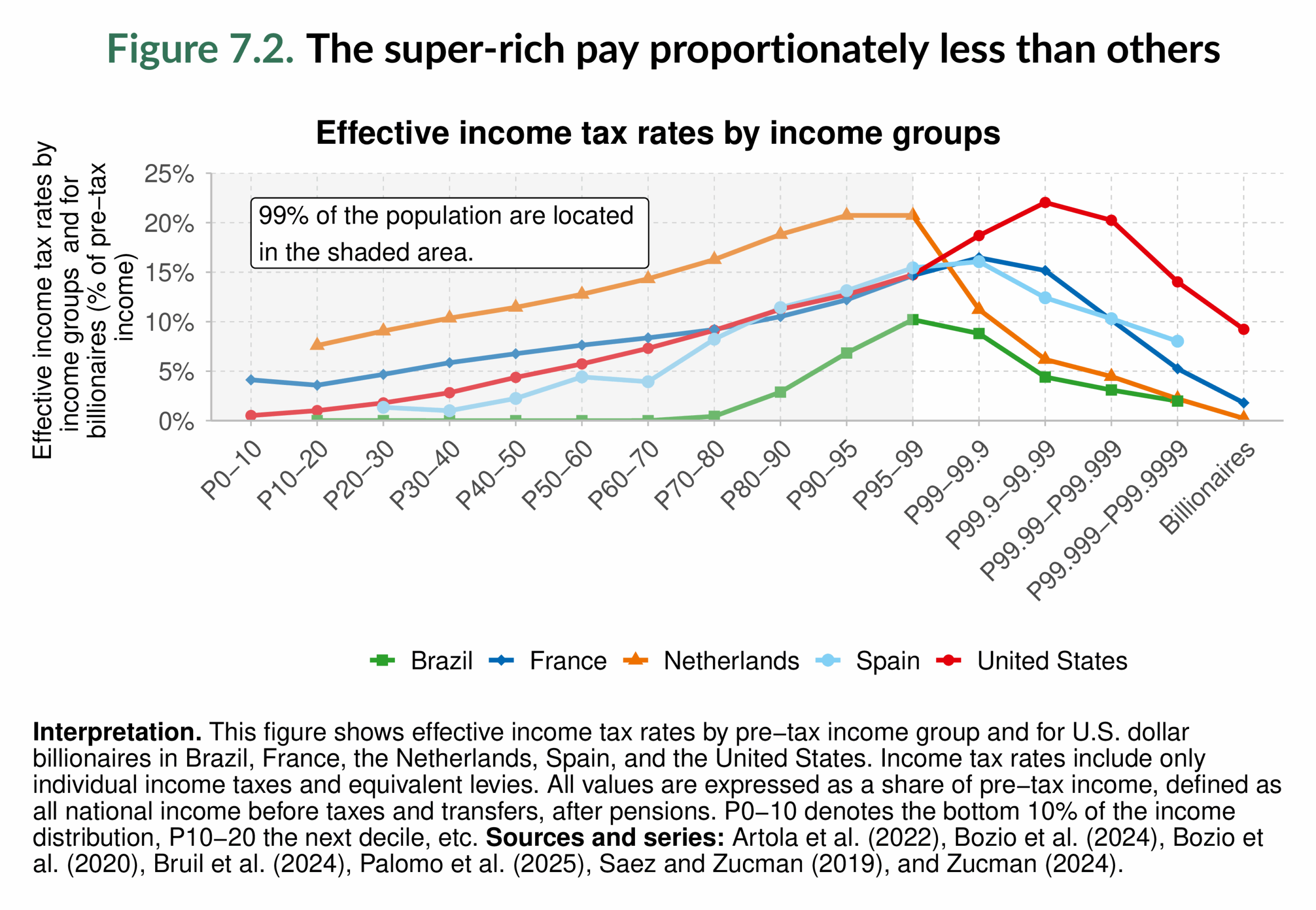

Wealth concentration has reached historic levels. Today, a few thousand multi-millionaires and billionaires command fortunes comparable to the annual incomes of entire countries. This raises a pressing question: are tax systems ensuring that those with the greatest means contribute their fair share to society? The evidence shows that they are not. In many countries, effective tax rates decline at the very top of the distribution. While middle- and upper-middle-income groups face stable or rising rates, the richest often pay proportionally less.

This chapter examines these issues. First, we explore why progressive taxation matters, showing its role in financing growth, reducing inequality, and safeguarding democracy. We then document regressivity at the top, where the wealthiest contribute proportionally less than lower-income households. Next, we consider how a minimum wealth tax could restore progressivity or at least prevent regressivity and raise the revenues necessary to decrease inequality. Finally, we highlight that international cooperation can increase the feasibility of reducing tax evasion in a world of mobile capital.

Why progressive taxation matters

A government with greater resources can invest more in public goods and productive projects that increase the well-being and opportunities of the population. Furthermore, taxes are not simply a way of raising revenue; they are one of the principal means for societies to determine who contributes to collective life and how. In a progressive tax system, higher-income and wealthier groups contribute proportionally more.

Progressive tax systems mobilize resources for public goods, reduce inequality, strengthen the legitimacy of tax systems by ensuring fairness, and limit the disproportionate political influence that extreme wealth can buy.

Figure 2.14–Figure 2.16 in Chapter 2 show why progressive taxation is important for redistribution. First, it can directly reduce inequality by securing larger contributions from those at the top. Second, it makes possible the funding of public goods, such as education, health, and social protection, which are key for reducing inequality (see Gethin (2023)) since they deliberately shift resources toward the middle and bottom of the distribution. Without progressive taxation, income gaps translate directly into unequal living standards.

A fairer tax system is also a more sustainable one. When citizens believe that everyone contributes according to their means, they are more willing to pay taxes and less likely to resist redistributive policies. This sense of tax consent is essential to sustaining social cohesion. Conversely, when households perceive that the wealthy can avoid or evade taxation while the burden falls disproportionately on them, resistance grows. Progressive taxation strengthens trust in government by making the system visibly fair: taxpayers see schools, hospitals, or infrastructure financed by collective contributions, and they see that the richest are not exempt. This legitimacy effect has profound implications for political stability.

Finally, Figure 7.1 highlights a way that unchecked wealth concentration can distort democracy (see Cagé (2024)). The top 0.01% in the United States now account for over 20% of charitable donations, steering much of philanthropy toward elite institutions or causes aligned with donors’ preferences. In France and South Korea, the richest 10% provide more than half of political donations. These patterns underscore how extreme wealth translates into political and cultural influence, undermining the principle of equal citizenship. Progressive taxation reduces these distortions by ensuring that great fortunes are less valuable as tools of political power.

Progressive taxation is not only a way to increase public revenue. It is also a mechanism to directly reduce inequality, fund redistributive public goods, foster social cohesion, promote economic growth, and safeguard the integrity of democratic representation.

Regressivity at the top

One of the most important facts highlighted in this report is that tax progressivity breaks down precisely where it should matter most: at the very top of the distribution. While tax systems are designed to appear progressive, effective rates often fall sharply for multi-millionaires and billionaires once we compare total taxes paid against their full economic income. Large parts of top incomes escape taxation.

Figure 7.2 illustrates one of the main paradoxes of modern tax systems: while tax codes in high-income countries are often designed to be progressive, they become regressive at the very top of the distribution (see Zucman (2024)). Regressivity emerges because the income tax fails at the top. In France and the Netherlands, billionaires’ effective income tax rate drops to near zero because of tax avoidance. In the United States, anti-avoidance rules keep billionaire rates somewhat higher, but they still fall sharply compared to upper-middle groups. Tax avoidance primarily operates through two channels (see Alstadsæter et al. (2023) and Zucman (2024)): (i) delaying or avoiding dividend distributions and capital gains realizations, and (ii) using holding companies and similar legal structures to accumulate earnings tax-free.

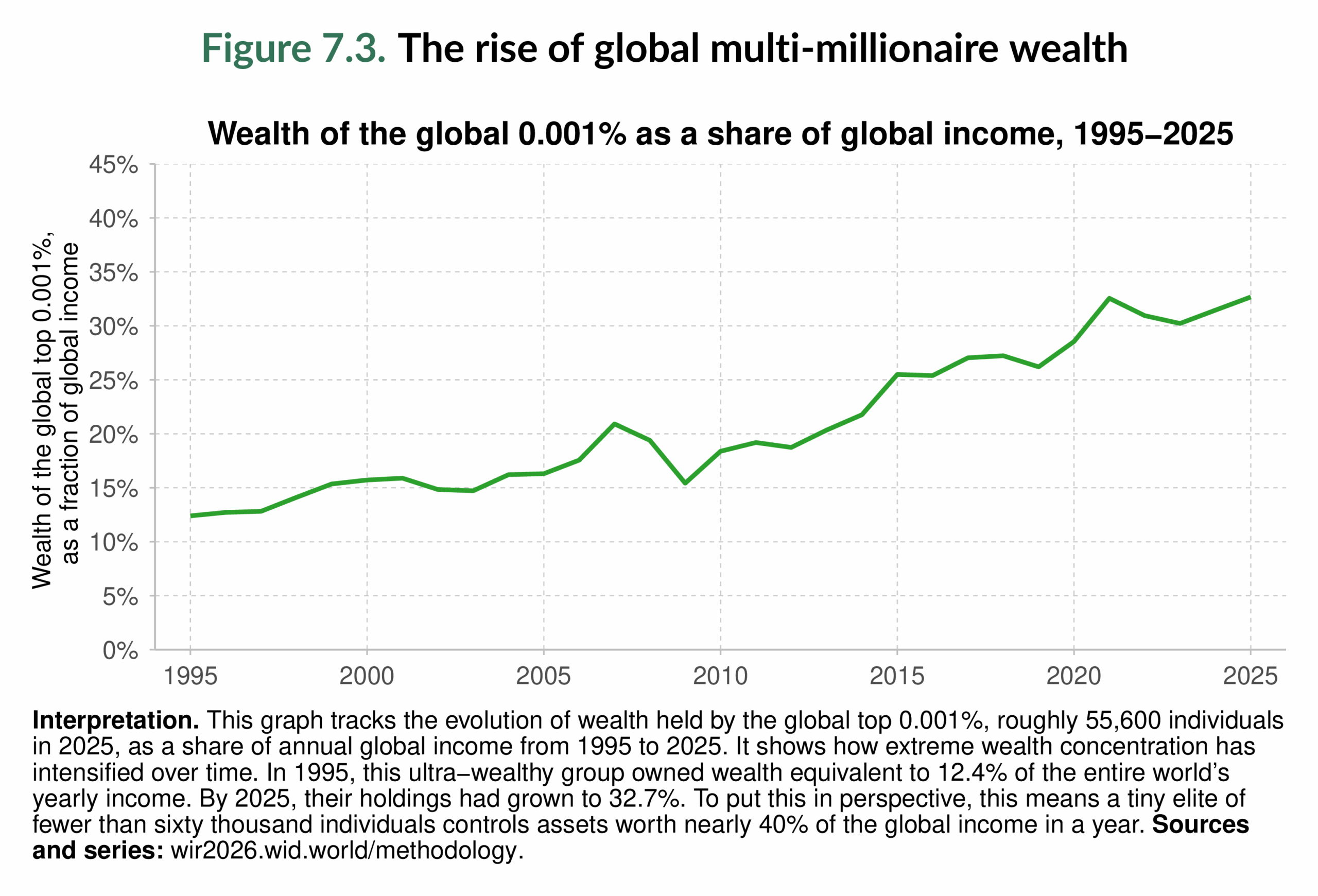

Figure 7.3 situates this regressivity in historical perspective. Over the past three decades, global multi-millionaire wealth has soared, tripling relative to world income (see Alstadsæter et al. (2023)). In 1995, the global top 0.001% held assets equivalent to 12% of global income. Three decades later, their share has nearly tripled, reaching 33% by 2025. Put differently, about sixty thousand individuals now control wealth worth one-third of the world’s combined income. Tax systems meant to fund public goods and reduce inequality instead reinforce concentration at the very top. Unless corrected, regressivity at the top will continue to erode both fiscal capacity and democratic cohesion.

Safeguarding progressivity at the top

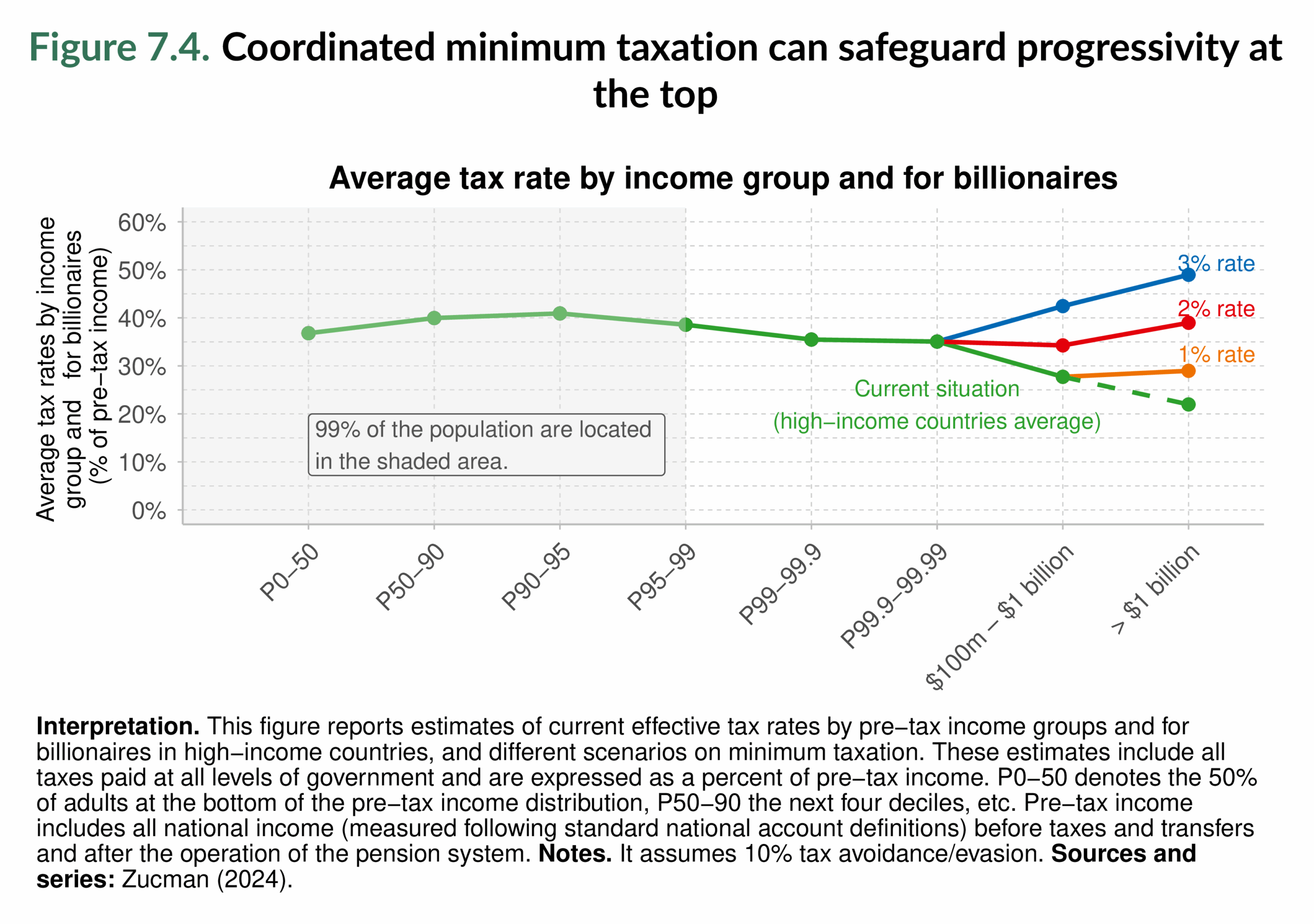

If today’s tax systems collapse into regressivity at the very top, the crucial question to ask is: how do we restore fairness? Figure 7.4 provides a straightforward answer: introduce a minimum wealth tax on centi-millionaires and billionaires (see Zucman (2024)). The figure simulates what would happen if governments in high-income countries implemented a tax of 1%, 2%, or 3% of wealth annually.

The results are striking. With no reform, billionaires face effective tax rates around 20%, well below the burden of households with lower incomes. A 1% wealth tax would modestly increase their contribution, but regressivity would remain. At 2%, the decline is essentially neutralized; centi-millionaires and billionaires would be brought back up to roughly the same tax burden as other taxpayers. At 3%, the system becomes modestly progressive again, with the very richest paying more than the rest.

A 2% tax rate is the minimum benchmark for safeguarding non-regressivity. This proposal builds on work by the EU Tax Observatory and the report titled “A Blueprint for a Coordinated Minimum Effective Taxation Standard for Ultra-High-Net-Worth Individuals”, prepared by Gabriel Zucman and commissioned by the Brazilian G20 presidency in 2024. The report shows that such a measure is technically feasible, administratively manageable, and politically transformative. A 2% minimum tax on global billionaires could raise between $200 and $250 billion annually from about 3,000 individuals worldwide, funds equivalent to the entire health budgets of many low-income countries combined.

Momentum for this idea has accelerated in several countries. Some examples are Brazil, South Africa, Spain, and France. Brazil placed the billionaire tax on the G20 agenda during its 2024 presidency. Spain has also taken a leadership role internationally, co-launching with Brazil and South Africa in 2025 a platform at the UN to build support for a global billionaire tax. France debated a 2% tax on fortunes above €100 million earlier in 2025: the National Assembly approved it, but the Senate rejected the bill. The issue in France is at the center of the political debate. In the United States, Senator Elizabeth Warren and others continue to advocate for the Ultra-Millionaire Tax Act, which proposes a 2% tax on net wealth above $50 million and a 3% total rate above $1 billion.

Regressivity at the top is not inevitable. With a minimum wealth tax, governments could restore progressivity, mobilize substantial resources, and rebuild the legitimacy of fiscal systems in the age of extreme wealth. Implementing such a tax is ultimately a question of political will, whether societies choose to confront the concentration of wealth and demand fairer contributions from those at the very top.

Tax justice and the potential of a global wealth tax

The case for a global wealth tax rests not only on technical feasibility but also on justice. The previous section showed that a 2% minimum tax on billionaires would neutralize regressivity at the very top, raising $200–250 billion annually. Yet focusing exclusively on billionaires risks leaving most of the ultra-rich tax base untouched. Billionaires are only the tip of the iceberg. Below them lies a larger group of centi-millionaires, those worth at least $100 million, whose fortunes allow them to minimize contributions in similar ways, but who would escape any billionaire-only tax.

Figure 7.5 highlights the scale of revenue that could be mobilized under different scenarios. A 2% global tax on centi-millionaires would generate more than $500 billion annually, equivalent to 0.45% of world GDP.12 A moderate 3% rate would raise about $754 billion (0.67% of world GDP), ensuring tax progressivity. An ambitious 5% tax could yield a staggering $1.3 trillion per year (1.11% of global GDP). These are not marginal adjustments. They are sums on a scale comparable to today’s global public spending on health, education, or climate adaptation. In other words, taxing a fraction of extreme private wealth could decisively expand governments’ fiscal capacity to address humanity’s most pressing needs. As N. K. Bharti et al. (2025) showed for the Indian case, taxing a tiny fraction of the very wealthy can fund transformative investments while leaving the vast majority of citizens untouched. The logic is the same globally: a modest tax on extreme

fortunes can deliver benefits for billions

Tax justice is both feasible and transformative. Taxing just 0.002% of adults worldwide could generate between 0.5% and 1.1% of global GDP in revenues. These resources could double public education budgets in low- and middle-income countries or finance large-scale climate programs. More than a technical tool, wealth taxation is a way of converting extreme private fortunes into shared investments for the collective good.

Figure 7.6 deepens the analysis regarding the baseline 2% minimum tax on centi-millionaires, illustrating the regional contrasts. East Asia alone, home to over 32,000 centi-millionaires, could generate a potential revenue of nearly $167 billion annually, surpassing the potential revenue of North America & Oceania ($142 billion). Europe could raise over $73 billion, while South & Southeast Asia could mobilize $63 billion. Even in regions with comparatively few ultra-rich individuals, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, a small number of centi-millionaires could still generate meaningful resources relative to their domestic economies.

To put these figures into perspective, the additional global $503 billion that could be raised annually with a 2% wealth tax on centi-millionaires is greater than the total GDP of many middle-income countries. This sum would be enough to fully cover the combined public debts of numerous low-income nations in one year or to substantially improve the economic prospects of millions of people. In short, taxing fewer than 100,000 individuals could transform the fiscal capacity of governments worldwide and significantly reduce inequality. It would also help to reduce the inequality of opportunities across regions (Figure 7.7).

Tax justice thus has both distributive and political dimensions. On the one hand, redirecting extreme private fortunes into public investments can help finance education, health, and climate resilience on a global scale, reducing inequality. On the other hand, ensuring that all ultra-rich individuals contribute proportionally rebuilds trust in taxation. Citizens are more willing to support fiscal systems when they see that the very richest, not just ordinary workers, carry their fair share.

Coordination between countries strengthens the feasibility of reducing tax evasion and avoidance

No matter how well designed national tax systems may be, their effectiveness can be undermined if wealth can easily cross borders. The fortunes of multi-millionaires can be highly mobile, often hidden through offshore structures or shifted toward jurisdictions with low or no taxation. This section highlights both the opportunities that emerge when states act together to prevent this, and the actions that can be implemented unilaterally to reduce tax evasion.

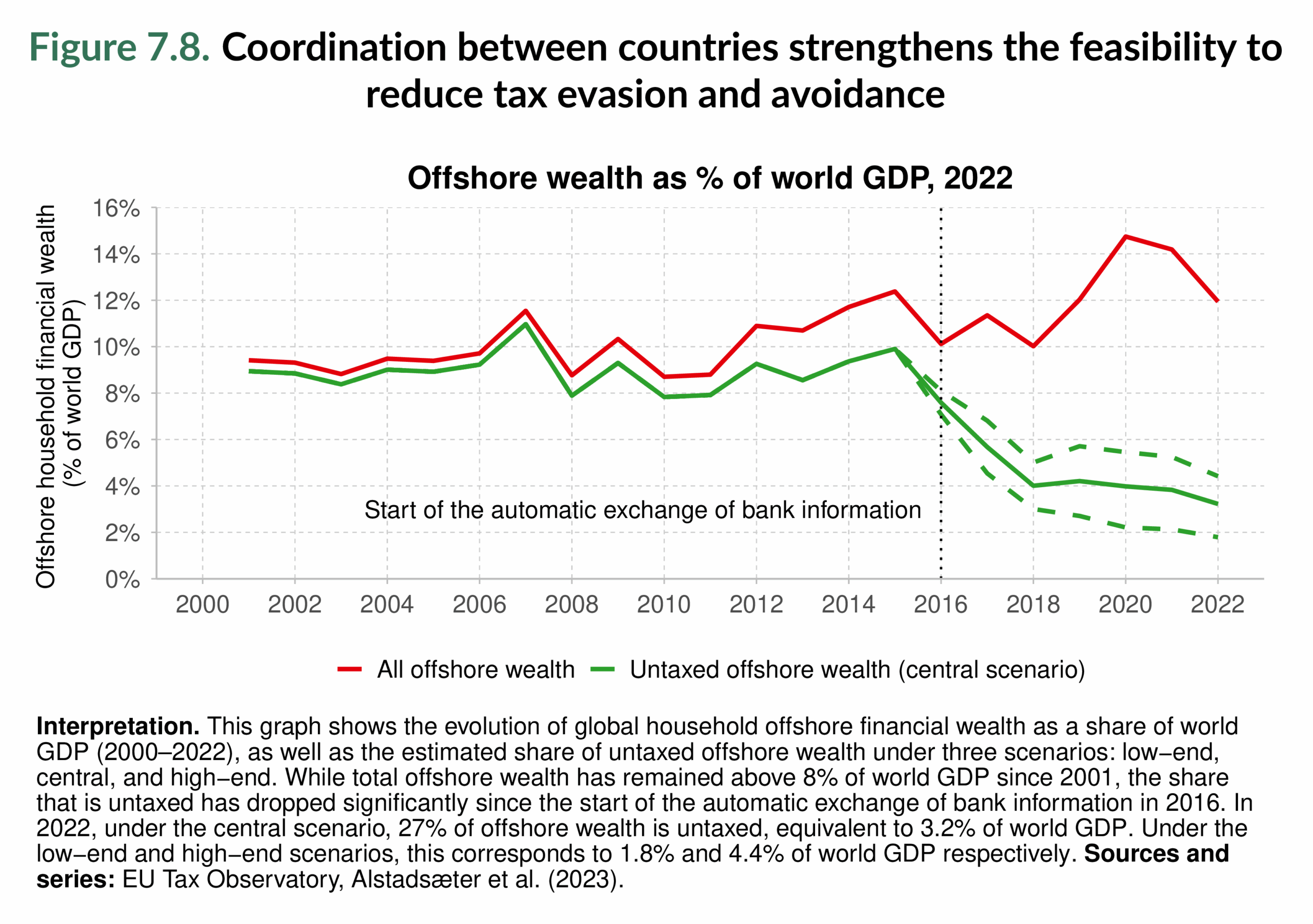

Figure 7.8 documents a turning point in the fight against offshore evasion. For decades, up to 90–95% of offshore wealth went undeclared, depriving governments of billions in revenues. After the introduction of automatic exchange of banking information in 2016 under the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard, this share fell dramatically. Still, by 2022, about 27% of offshore wealth remained untaxed, roughly 3.2% of world GDP. The lesson is clear: global cooperation has proven possible and efficient in cutting offshore evasion by a factor of three in less than ten years. This decline in non-compliance represents a significant achievement and demonstrates that rapid progress on tax evasion is possible when there is sufficient political will.

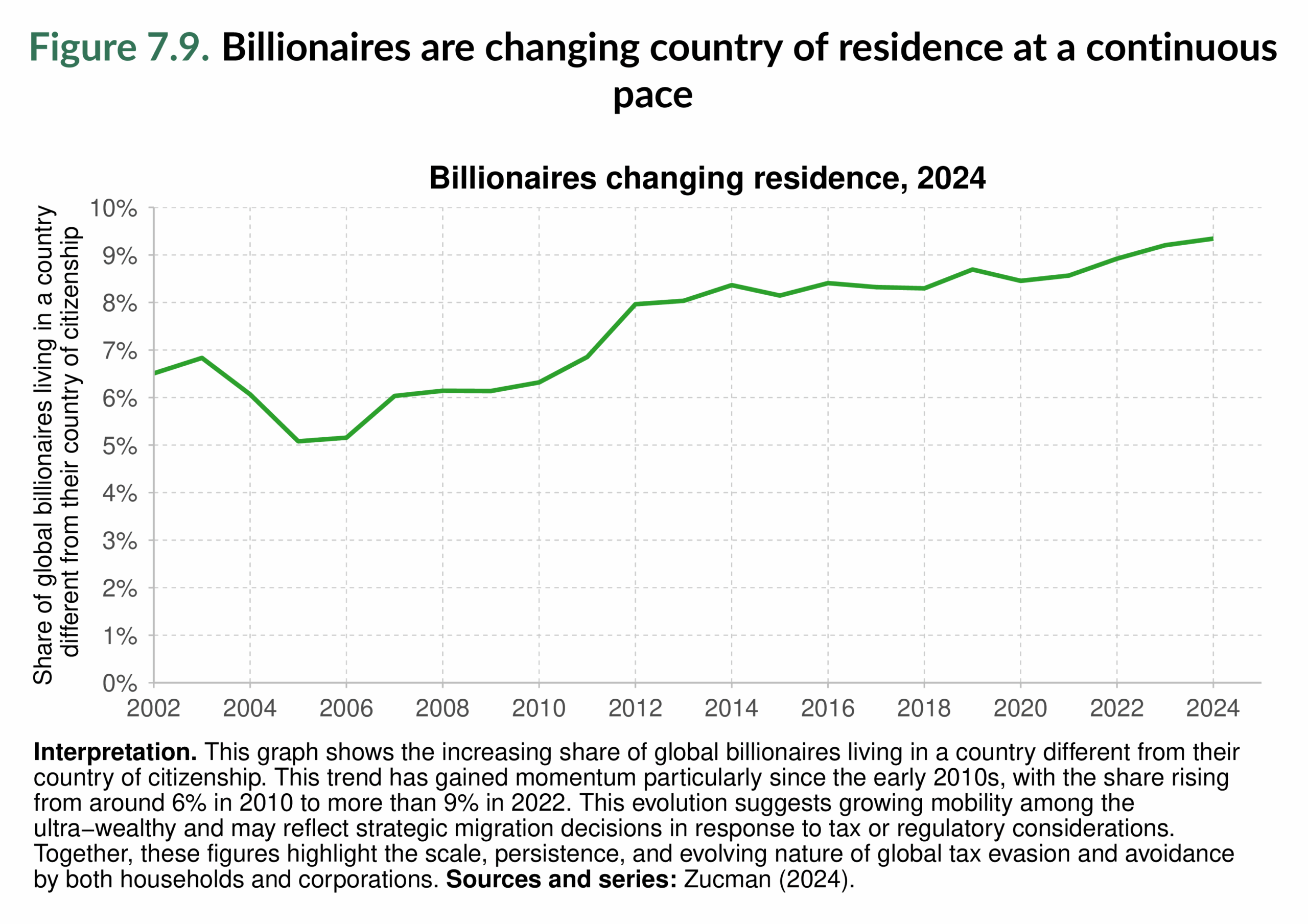

Figure 7.9 highlights billionaire mobility: the share of billionaires living outside their country of citizenship rose from 6% in 2002 to over 9% in 2024. While most remain at home, relocation to low-tax jurisdictions threatens the integrity of national tax systems. Policy responses can follow two distinct paths. One option is partial international coordination through a “tax collector of last resort” rule, which allows a billionaire’s home country to step in and collect additional taxes when wealth is shifted abroad and taxed at very low rates. Another option is for countries to act independently through exit taxes, which require individuals to settle their tax bill on accumulated wealth the moment they change residence.

It is crucial to note that, while cooperation is important, waiting for a global consensus regarding a 2% wealth tax on centi-millionaires is unnecessary (see Zucman (2024)). The infrastructure for cross-border cooperation (automatic bank information exchange, beneficial ownership registries) is already in place, and enforcement mechanisms like exit taxes or “tax collector of last resort” rules could limit incentives for relocation. Many countries have already implemented rules to limit tax-driven changes in residency of high-net-worth individuals, including exit taxes. Countries implementing the minimum tax standard could build on these rules and strengthen them.

The broader lesson is twofold. First, coordination works: automatic information exchange and minimum taxation standards have already reshaped global tax governance. Second, leadership matters: a coalition of willing countries can move first, raising revenues and demonstrating feasibility and benefits without waiting for universal agreement. Given the globalization of wealth, tax justice is strengthened both with multilateral ambition and determined national action.

Main takeaways

This chapter has explored the role and potential of progressive taxation in an era of unprecedented wealth concentration. The starting point was to show why progressive taxation matters. Tax systems that mobilize revenues sustain growth by financing education, health, and infrastructure; they reduce inequality through redistributive spending; they build legitimacy by strengthening tax consent and social cohesion; and they curb political capture by limiting the unequal influence of the ultra-rich.

However, tax progressivity collapses precisely where it should matter most: at the very top. Figure 7.2 and Figure 7.3 demonstrate how effective tax rates fall for multi-millionaires and billionaires, even as their fortunes expand. Solutions exist. Figure 7.4 shows that a 2% minimum wealth tax would halt regressivity, while higher rates could restore progressivity. Current experiences in Brazil, South Africa, Spain, and France illustrate both the fertility of debates surrounding such measures and the feasibility of their implementation.

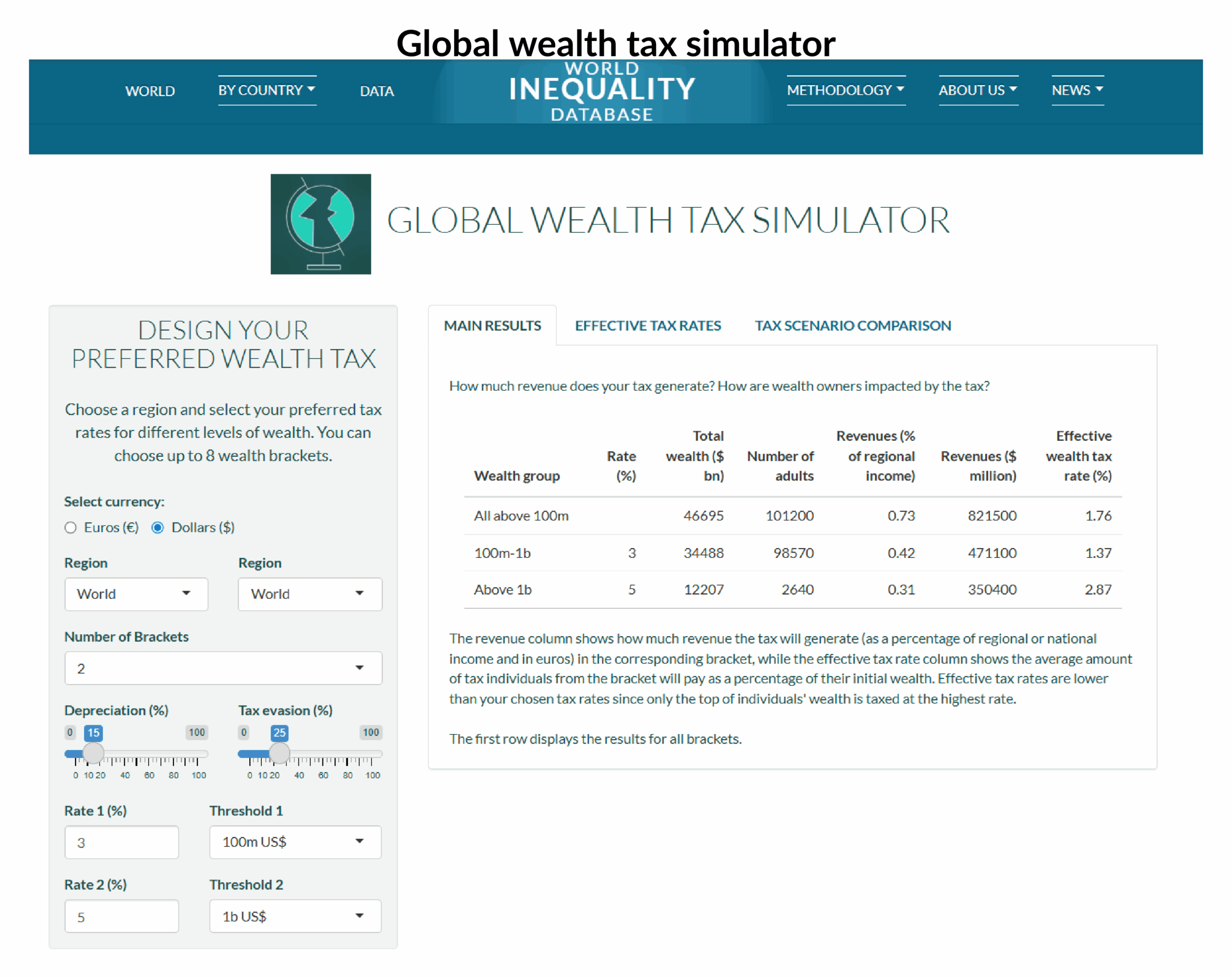

Figure 7.5 and Figure 7.6 show tax justice proposals using the Global Wealth Tax Simulator, an interactive tool developed by the World Inequality Lab. They demonstrate how taxing a tiny fraction of the population can finance transformative investments to address gross inequalities of opportunity (Figure 7.7). Finally, Figure 7.8 and Figure 7.9 underline that international cooperation is both necessary and highly effective in reducing tax evasion and avoidance. A coalition of the willing could limit tax evasion by targeting wealth mobility and strengthening global fiscal sovereignty.

Box 7.1: Explore the Global Wealth Tax Simulator

Debates over taxing extreme wealth often feel abstract. How much revenue could be raised? How many individuals would be affected? What level of tax would ensure fairness? To make these questions concrete, the World Inequality Lab has developed the Global Wealth Tax Simulator, an interactive tool that allows anyone—from researchers, policymakers, or journalists, to ordinary citizens—to design their own wealth tax.

The simulator works by enabling users to choose tax evasion thresholds and rates. It then calculates three primary outcomes: total revenues raised, the effective tax rates, and the number of individuals affected. For example, a global tax of 2% on fortunes above $100 million would generate nearly half a trillion dollars annually, while affecting only a few thousand people worldwide.

Beyond these numerical projections, the tool offers a way to visualize tax justice through tables and graphs. It shows how modest contributions from the very top of the distribution could transform public finances . The simulator invites engagement and delivers a simple message: the resources exist to reduce inequality and strengthen public goods. The question is no longer one of technical feasibility, but political will.

1 The World Inequality Lab created the Global Wealth Tax Simulator (see Box 7.1) to help design wealth taxes. It allows users to model scenarios and visualize the potential revenues.