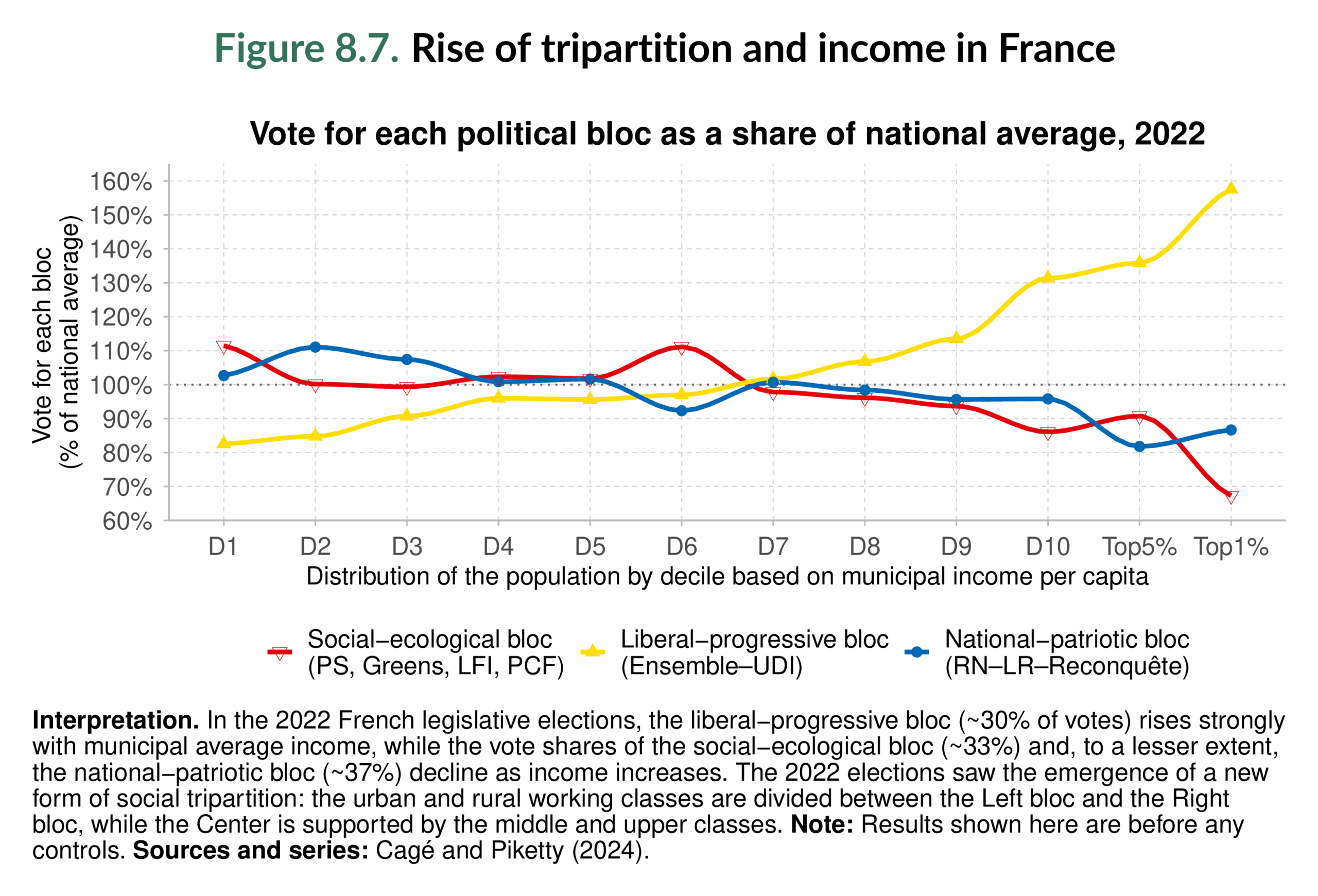

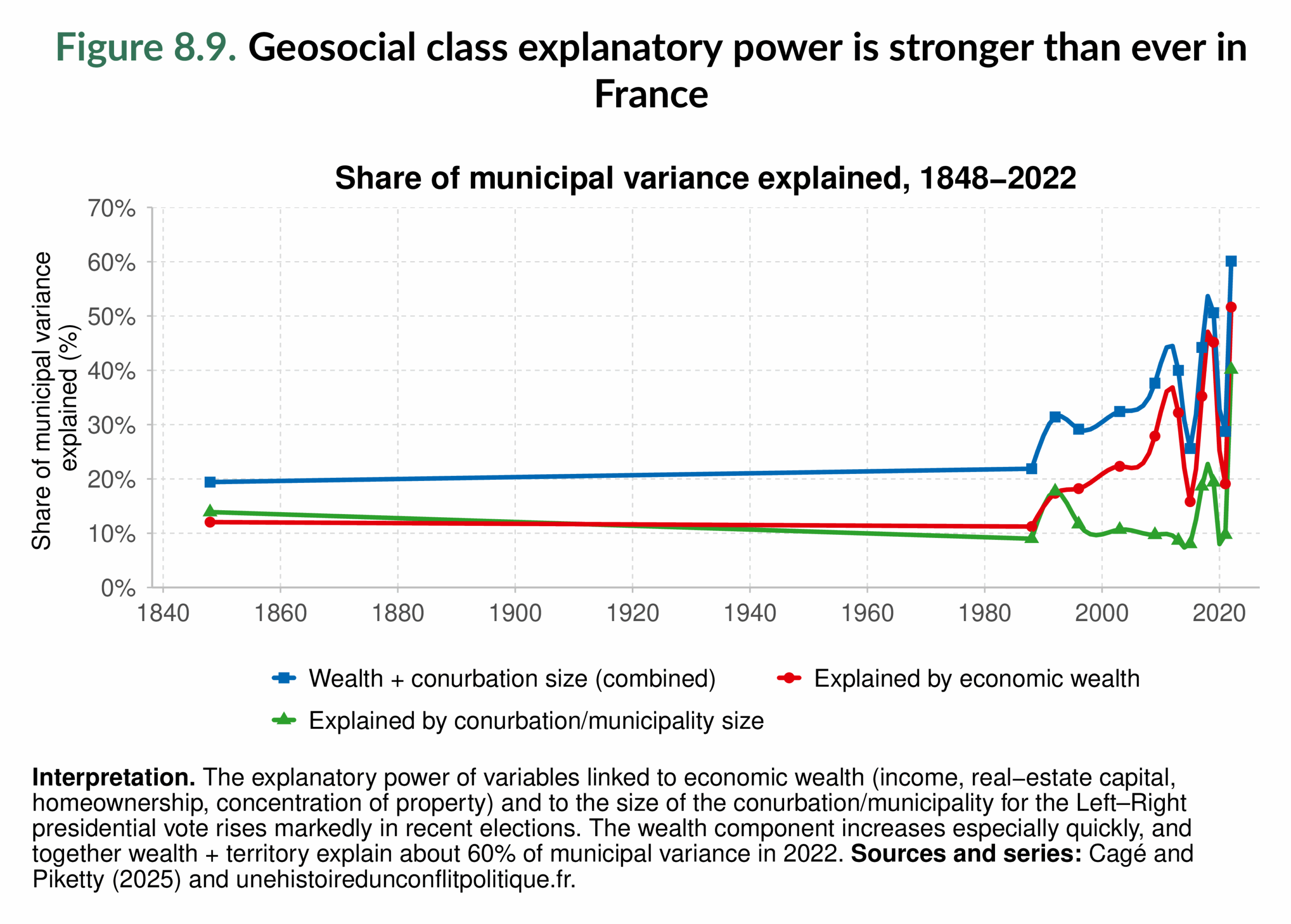

This chapter examines how political cleavages have evolved and what these transformations reveal about inequality and democracy. We begin with the decline of political working-class representation (Figure 8.1). We then turn to the disconnection of income and education political divides in Western democracies, which has produced “multi-elite” party systems where educated elites lean left and affluent elites remain on the right (Figure 8.2–Figure 8.5). Figure 8.6 widens the lens to non-Western democracies, where cleavages often follow ethnic, religious, or regional lines rather than the income–education divide. Figure 8.7–Figure 8.8 highlight the resurgence of territorial conflict in Western democracies. Figure 8.9 concludes by emphasizing the growing explanatory power of geosocial class, the combination of wealth and conurbation size, in determining political outcomes.

Political representation of the working class is low and declining

This section highlights a central paradox of modern democracies: while the principle of universal suffrage promises equal political voice, the working class has been persistently underrepresented in institutions of power, and this dimension of inequality has deepened in recent decades. Figure 8.1 documents the long-run decline of working-class representation in parliaments across France, the United Kingdom, and the United States1. The figure plots the share of MPs whose last occupation before entering politics was a manual or blue-collar job, compared to the total number of MPs in each country. It shows that working-class representation has always been low and has further deteriorated in recent decades.

This disconnect between the social composition of legislative bodies and that of the electorate illustrates a central dimension of political inequality: the growing gap in descriptive representation. The erosion of political representation reshapes political priorities. Legislators from working-class origins are more likely to push for redistribution, stronger labor rights, and protections for vulnerable groups. Their absence narrows the scope of policy debate, leaving structural inequalities unaddressed.

The result is a political system that, much like the trends documented in previous chapters, channels power and resources to the top of the distribution. Democracies today risk entrenching a system in which the working majority is politically marginalized.

Income and education divides have disconnected in Western democracies

A possible explanation for this persistent underrepresentation of the working class is the rise of “multiple-elites” political systems, where different elite groups, those with high education and those with high income, dominate opposing political camps. Figure 8.2 through Figure 8.5 shed light on this transformation over the past half-century for twenty-one Western democracies. They reveal the gradual disconnection of income and education divides, the reversal of the educational cleavage, and the emergence of new political alignments that increasingly set different elite groups in opposition to one another.

Figure 8.2 illustrates one of the most important shifts in the political landscapes of Western democracies over the past seven decades: the gradual uncoupling of income and education as determinants of the vote. In the 1950s and 1960s, politics in most Western democracies was organized along a relatively straightforward class-based axis. Low-income and low-educated voters rallied behind social democratic, socialist, and communist parties (“left-wing” parties), while high-income and highly educated groups supported conservative, Christian democratic, and liberal parties (“right-wing” parties). In the past decades, however, these two groups have diverged sharply.

On the one hand, education has become a strong predictor of support for the left. Higher-educated voters increasingly lean toward left parties, to the point where, since the 1990s, the top 10% of educated voters are systematically more left-leaning than the less educated majority. On the other hand, income remains firmly linked to the right. The top 10% of earners continue to prefer conservative or right-wing parties. The gap with the bottom 90% has remained negative: top-income voters are consistently less likely to support the left. This transition highlights a shift from “class-based” to “multi-elite” party systems, which now feature opposing camps comprising an educated “Brahmin left” and an affluent “merchant right” (see Gethin, Martínez-Toledano, and Piketty (2022); Gethin, Martínez-Toledano, and Piketty (2021); Gethin and Martínez-Toledano (2025)).

This structural transformation is closely related to educational expansion and the ensuing “complexification” of the occupational structure. By way of illustration, many high-degree but relatively low-income voters (e.g., teachers or nurses) currently vote for the left, while many voters with lower degrees but relatively higher income (e.g., self-employed or truck drivers) tend to vote for the right.

Importantly, this transformation has not been restricted to a few countries. It has unfolded across almost all twenty-one Western democracies included in the World Political Cleavages and Inequality Database, despite wide differences in their histories, institutions, and party structures. This common transformation has been closely linked not only to the rise of a new sociocultural axis of political conflict, but also to the convergence of parties on economic policy, political fragmentation, economic development, and educational progress (see Gethin and Martínez-Toledano (2025)).

Figure 8.3 documents the remarkable reversal of educational divides across different Western democracies. In the postwar decades, voters with low levels of education were the backbone of left-wing parties, while the highly educated leaned right. Today, the opposite holds: highly educated voters now disproportionately vote more for the left, while the less educated often support conservative parties.

This reversal has transformed left-wing parties from representing the industrial working class in the past into coalitions anchored in the educated middle and upper-middle classes in the present. These left parties increasingly attract highly educated “sociocultural professionals”, such as education and healthcare workers, public sector employees, and urban elites, whose concerns and political priorities extend beyond redistribution to issues such as climate change, minority rights, and gender equality. Meanwhile, less educated voters have turned toward conservative platforms.

This pattern is visible in nearly all Western democracies, though with varying intensity. Portugal and Ireland remain partial exceptions, with smaller or delayed reversals. Yet the broader trend is clear: education, once a strong determinant of support for conservative parties, has become a defining predictor of left voting in most Western democracies.

Contrary to education, the income divide has remained relatively stable. Figure 8.4 shows that higher-income voters continue to lean right. This enduring divide has meant that even as educational elites shifted left, affluent groups have largely remained on the right.

Yet the income divide has not been static. In many Western democracies, the influence of income on the vote declined during the late 20th century, as party competition increasingly shifted toward cultural issues. A striking case is the United States. In recent elections, high-income voters have shifted to the Democratic Party, becoming more likely than low-income groups to support the Democrats. This shift represents a historic reversal of the classic postwar pattern, which highlights how far the U.S. has moved toward a “high-income-left” coalition and illustrates the weight of sociocultural divides in shaping political conflict.

Figure 8.5 brings these dynamics together by plotting income and education gradients simultaneously. In the 1960s, parties lined up along a diagonal: left-wing parties were supported by low-income and less educated voters, while right-wing parties drew support from high-income and highly educated voters. By 2000–2025, this alignment has fractured. Parties now cluster across different quadrants. Green parties occupy the high-education section but do not distinguish themselves in terms of income. Anti-immigration movements dominate the low-education space, appealing to both low- and high-income groups. Conservatives remain rooted in high-income voters but now draw support from segments of the less educated. Social democrats, socialists, and other left-wing parties continue to be supported by low-income groups but now attract a greater faction of higher-educated voters.

This fragmentation reveals that income and education now pull voters in different directions. The result is a fractured electorate where pro-redistribution coalitions are harder to sustain. The disconnection of income and education cleavages weakens the political potential to address inequality.

Income and education are not the only axes of political conflict in these Western democracies. Other divides (age, religion, and gender) continue to shape electoral behavior. With the exception of gender, which has undergone a reversal similar to education (women now lean more left than men), there is little evidence of generalized realignment along these other dimensions. Age, religiosity, and church attendance remain stable predictors of conservative voting, while younger, urban, and secular electorates lean to the left. Geography, particularly the rural–urban divide, has become increasingly salient. Its dynamics are analyzed in detail in Figure 8.7–Figure 8.8.

Figure 8.2–Figure 8.5 provide an explanation of why the decline of working-class representation in Western democracies, shown in Figure 8.1, has not been reversed. Today, politics is dominated by multiple elites, leaving workers politically fragmented and underrepresented. The fragmentation of electorates makes redistributive coalitions harder to sustain, even as inequality has risen sharply. The concentration of political influence among high earners and the highly educated mirrors the concentration of economic resources at the top. Political systems remain deeply structured by inequality, but the disconnection of income and education has made it harder for majorities to mobilize against it.

Non-Western democracies have different structures of political division

The patterns documented in Figure 8.2–Figure 8.5 show how twenty-one Western democracies have converged toward multi-elite systems, with education and income pointing in different political directions. In non-Western democracies, political cleavages follow much more diverse trajectories. Instead of a common move toward the “Brahmin left versus merchant right” configuration, income and education often remain aligned (see Figure 8.6), and other dimensions of political conflict (ethnicity, religion, caste, or region) play a more important role.

The evidence in Figure 8.6 for thirty-four non-Western democracies shows that income and education are closely aligned in determining electoral behavior. However, the strength of class divides varies widely, ranging from nearly absent in India, Indonesia, and Costa Rica, to exceptionally strong in Argentina, South Africa, and Poland.

The diversity of outcomes highlights how inequality interacts with national contexts. In some countries, income and education remain tightly linked to electoral behavior, unlike the Western reversal. In others, ethnicity, religion, or regional divides are more relevant dimensions of political conflict. The key insight is that there is no single trajectory of political realignment outside of the Western democracies. Socioeconomic divides are stronger or weaker depending on how they interact with other dimensions of political conflict. In South Africa, for instance, race remains a powerful determinant of political alignment, while in India, caste and religious identities significantly overlap with income and education divides. In Brazil and other Latin American democracies, class conflict continues to shape electoral behavior, but it often intersects with regional divides and legacies of inequality rooted in colonial history.

The reversal of the education cleavage which has been so central to Western democracies is much less common in non-Western democracies. This underscores that the multiple-elites trend is a localized rather than global phenomenon. Political cleavages are reshaped differently beyond the West, depending on historical legacies and institutional contexts.

The return of geography in political conflict: regional and rural–urban cleavages

Alongside the disconnection of income and education divides, geography has re-emerged as a central axis of political conflict (see Cagé and Piketty (2024)). Figure 8.7 and Figure 8.8 show how regional and rural–urban cleavages have deepened in recent decades, particularly in France. These divides recall earlier historical moments when territory shaped politics, but their renewed intensity has profound implications for today’s democracies. Preliminary evidence suggests that this finding also applies to other advanced democracies (e.g., the U.S., Britain, and Germany). In the case of France, gaps in political affiliations between large metropolitan centers and smaller towns have reached levels unseen in a century. Unequal access to public services (education, health, transportation, and other infrastructures), job opportunities, and exposure to trade shocks have fractured social cohesion and weakened the coalitions necessary for redistributive reform. As a consequence, working-class voters are now fragmented across parties on both sides of the aisle or left without strong representation, which limits their political influence and entrenches inequality. In order to reactivate the redistributive coalitions of the postwar era, it is critical to design more ambitious policy platforms that benefit all territories, as they successfully did in the past.

Figure 8.8 tracks the long-run evolution of the urban–rural divide in France. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, large cities leaned strongly toward the left, while rural areas favored conservatives. During the postwar decades, however, this gap narrowed, as class rather than geography structured political competition. By the 1990s, the pattern shifted again. Urban areas, with their diversified economies and higher education levels, increasingly supported left parties. Rural regions and small towns gravitated toward conservative parties. The most recent elections reveal the sharpest territorial split in over a century, with urban centers voting overwhelmingly for the left, while rural areas rallied to the right.

Figure 8.7 highlights how this cleavage has formed into a tripartite system in France (see Cagé and Piketty (2025)). The liberal-progressive bloc is heavily concentrated among the highest-income voters, particularly in affluent urban centers. The social-ecological (left) bloc draws support from diverse urban and younger populations, while the national-patriotic (right) bloc dominates among rural and peri-urban voters. This division fragments the working classes: urban workers lean left, while rural and small-town workers turn to the right.

The implications are far-reaching. Territorial divides complicate the possibility of broad redistributive coalitions by splitting working-class voters along geographic lines. As with the disconnection of income and education cleavages, geography fragments potential majorities for redistribution. France exemplifies this process, but similar dynamics are visible across Western democracies. Geography, once a muted force, has returned as a defining feature of political competition, reshaping how inequality translates into politics.

The explanatory power of geosocial class is stronger than ever

Now we turn to the growing importance of geosocial class, the combination of socioeconomic status and territorial location, in shaping electoral behavior (see Cagé and Piketty (2025)). Figure 8.9 traces this relationship in France from the mid-19th century to the present and shows that its explanatory power has never been as strong as it is today.

In France, geosocial class has influenced voting more in recent elections than ever before. This shows that factors like rural versus urban location, wealth, and types of jobs continue to shape politics more strongly than geography or identity. This finding contradicts the idea that politics has become dominated by purely cultural identity struggles. Instead, material and territorial inequalities remain powerful forces shaping electoral behavior.

Placed in the broader perspective of this report, the rise of geosocial class mirrors the dynamics of economic inequality documented in previous chapters. Electoral geography has become a mirror of inequality itself, demonstrating that democratic conflict remains deeply rooted in wealth inequality.

Main takeaways

The evidence presented in this chapter paints a clear picture: political cleavages in Western democracies have been profoundly restructured since the postwar years. Working-class representation in legislative bodies has always been low and has deteriorated further in recent decades (Figure 8.1). This exclusion mirrors the broader inequalities in income and wealth documented in earlier chapters and highlights how political voice itself has become more unequal.

Figure 8.2–Figure 8.5 provide an explanation for this phenomenon. The disconnection of income and education has given rise to multi-elite party systems, with highly educated voters shifting left and high-earning voters remaining aligned with the right. The result is a “Brahmin left” versus “merchant right” structure, in which different elites dominate opposing coalitions and working-class voters are increasingly fragmented or underrepresented.

Beyond income and education, other divides, such as religion or age, remain important but largely stable for Western democracies. Only gender has shown a reversal comparable to education, with women now leaning more left than men. Geography , however, has re-emerged as a powerful cleavage (Figure 8.7–Figure 8.8), splitting electorates between metropolitan centers and rural peripheries. This territorial dimension deepens the fragmentation of working-class voters and complicates redistributive coalition-building.

Importantly, the explanatory power of geosocial class has never been greater (Figure 8.9). Economic resources and territorial location together explain more of the variance in French electoral behavior today than at any point in the past 170 years. Political conflict remains anchored in structural inequalities. Electoral geography has become a mirror of economic divides, underscoring that democracy and inequality are deeply interrelated; the way that one evolves affects the other.

As for non-Western democracies, there is no common pattern, but rather a diversity of political profiles. In many countries, income and education remain closely aligned. Socioeconomic divides are stronger or weaker depending on how they interact with other dimensions of political conflict, such as ethnicity, caste, and regional identities. Unlike Western democracies, the multiple-elites system is far less common. This diversity underscores the fact that, although inequality shapes politics everywhere, the cleavages through which it operates are always mediated by local contexts.

1 See Cagé (2024).